What To Read As You Slowly Lose Your Mind

The Epistolary Novels of Saul Bellow, Rainer Maria Rilke, and Fyodor Dostoevsky

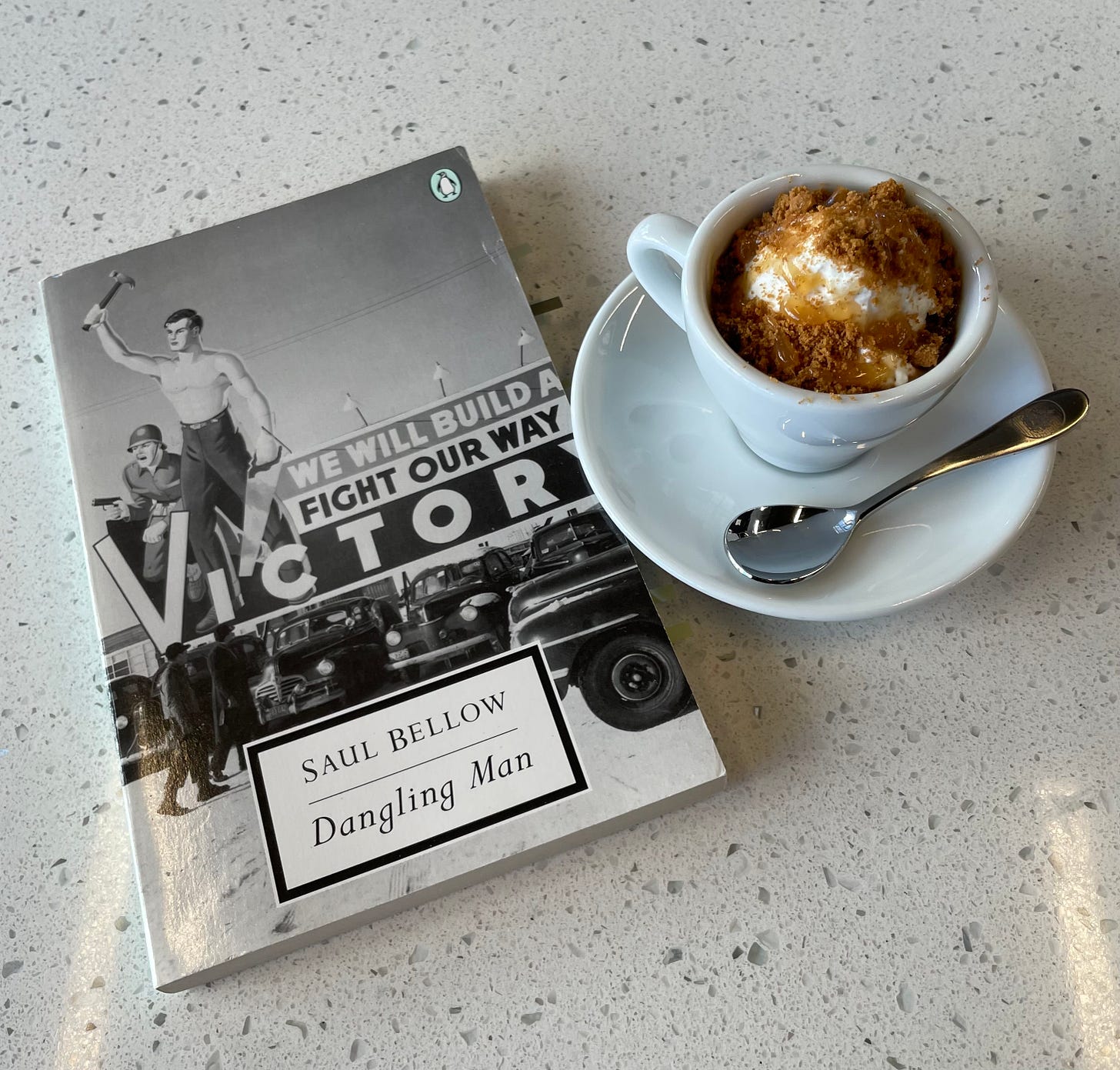

Dangling Man (1944) by Saul Bellow

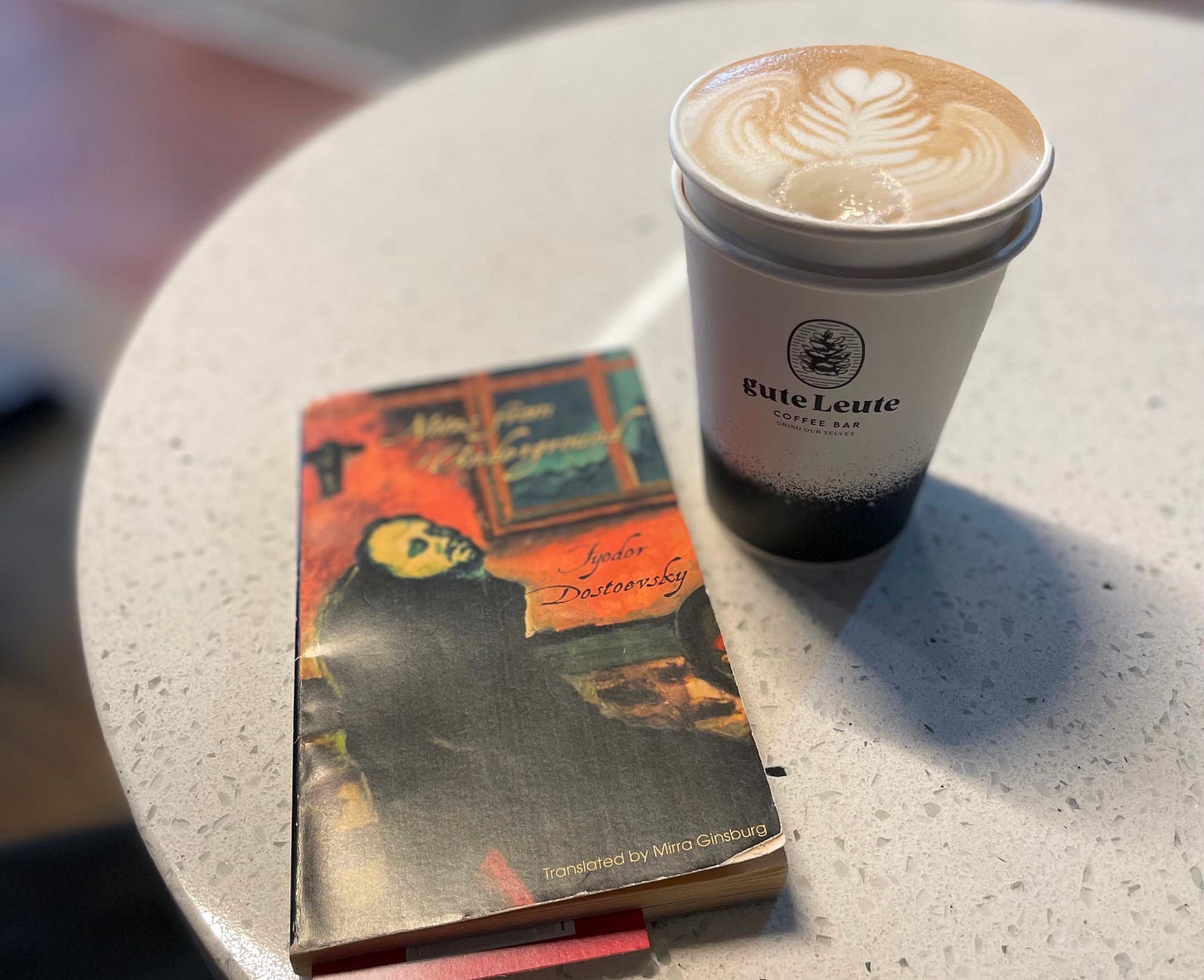

Notes From Underground (1864) by Fyodor Dostoevsky [trans. Mirra Ginsberg]

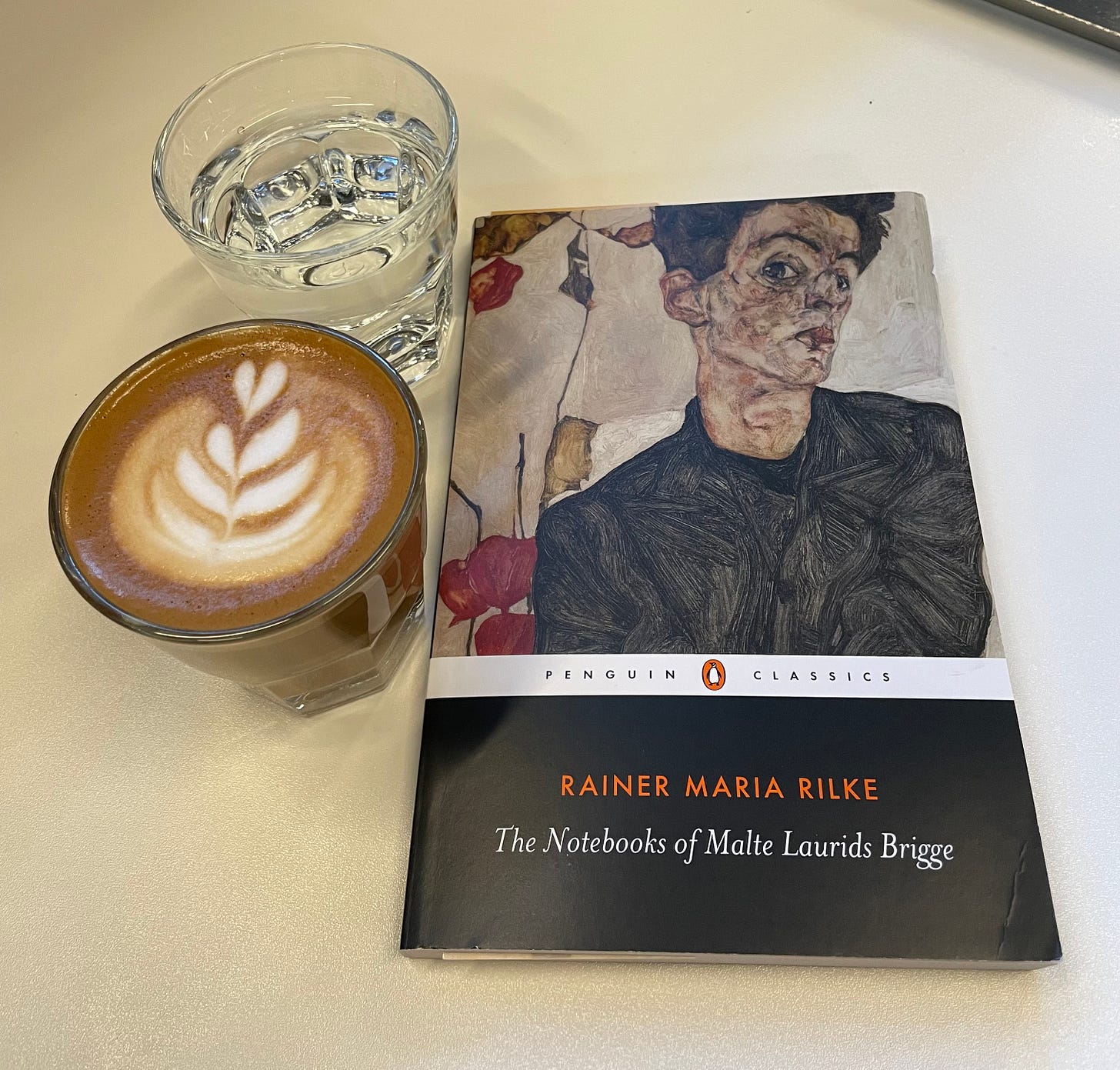

The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge (1910) by Rainer Maria Rilke [trans. Michael Hulse]

I am a sick man… I am a spiteful man. An unattractive man. —Notes From Underground, first page

I have thought of going to work, but I am unwilling to admit that I do not know how to use my freedom and have to embrace the flunkydom of a job because I have no resources—in a word, no character. … There is nothing to do but wait, or dangle, and grow more and more dispirited. It is perfectly clear to me that I am deteriorating, storing bitterness and spite which eat like acids at my endowment of generosity and good will. —Dangling Man, p.12

I prayed to have my childhood, and it has come back again, and I sense that it is as heavy a burden as it was then, and that growing older has served no purpose at all. —The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Bridge, Section 20, p. 42

I only meant to read Dangling Man. It was short, it was Saul Bellow, and it seemed like the kind of moody, introspective novel that pairs well with a cup of tea1 and a stretch of unstructured time. But like so many quiet little books, it turned out to be a trapdoor. Before I knew it, I’d fallen down a rabbit hole of bitter, bookish men narrating their own unraveling.

To make sense of Joseph—the titular dangling man—I found myself revisiting Dostoevsky’s Notes From Underground and pushing through Rainer Maria Rilke’s dense and dreamy The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge. All three books are diaries of lonely men stuck in cities, stuck in themselves, and stuck in time. They made me reflect not only on the through-lines of literary tradition, but on my own moments of dangling—jobless, uncertain, and slowly going feral in a Hyde Park apartment.2

This is the story of three diarists, one cold Chicago winter, and how I accidentally read a century of male existential despair just to understand one man’s slow descent into madness.

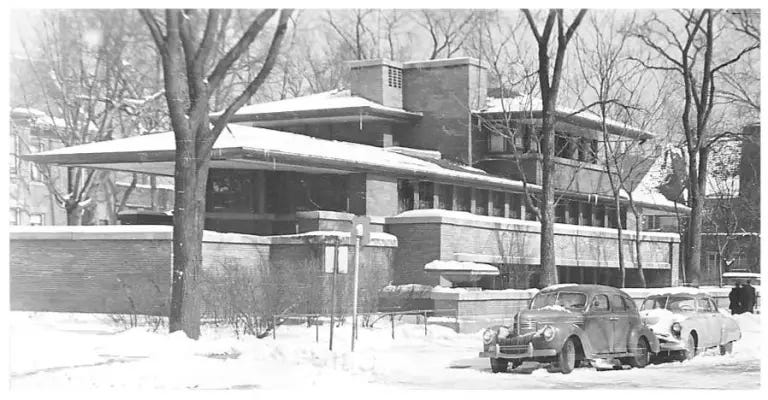

I love Chicago winters.

They’re different, now, and have been growing warmer and more impetuous since I moved away in 2016. But I love the winters of my youth.

I live in the DMV now, which doesn’t have proper winters. There’s a season that is generally colder than the rest of the year, and occasionally it will snow. The snow melts within a few days, usually. Sleet is the predominant precipitation. Spring in DC, Maryland, and Virginia is inordinately lovely. The cherry blossoms, the magnolias, the azaleas, eastern redbuds, every dead-looking stick suddenly shocked into beauty. It’s the region’s best season, but every year I imagine how much more satisfying it would be if it followed a real, solid winter.

Chicago winters are long and almost as brutal as they are given credit for. Chicagoans pride themselves on the toughness the winters engender, but in reality, we’re soft compared to Upper Peninsular Michiganders, most Sconnies, and Montrealers.3 It gets cold in late September, really cold by Thanksgiving, and stays cold until April. A weariness sets in around early February, when the fresh white snow of New Year’s turns grey, crunchy, plowed into great dense mounds of filthy ice that pile up on every curb, taking on almost architectural permanence. They are structures to be navigated around. The compacted ancient snow on the ground seems to bear no resemblance to the fluffy white flakes that pour inexorably down, buffeted and multiplied by the wind coming off Lake Michigan.

When the cold finally breaks, the city comes alive. It may still be wet and grey but there’s a new lightness in every breast. Strangers smile at each other. The relief is immense.

Dangling Man is the perfect Chicago winter novel. It is diaristic, taking place between December 15, 1942 and April 9, 1943. This is Saul Bellow’s debut novel, and it lacks some of the exuberance that is characteristic of his later prose, the paragraphs bursting with adjectives stacked upon adjectives, as if his every subject were so full of life that to merely describe it leaves one breathless. But there are still lovely passages that capture the essence of each facet of winter.

I didn’t know about its seasonality when I started reading it. It was luck that I started reading it on January 21 and finished it on March 11, 2025.

Dangling Man is the diary of Joseph, a 28 year old Canadian in Chicago who has been called up by the draft board to serve in World War II, but his induction into the army is delayed due to bureaucratic issues downstream of his immigration status. Unemployed and unable to seek new employment due to his draft status, Joseph lives off his wife, Iva, and sleepwalks through his days. Joseph and Iva live in a room in a boarding house in the Hyde Park neighborhood (where the University of Chicago is located), a step down from the flat they lived in before he was sorta-kinda drafted. Over the course of a year of “dangling” in bureaucratic purgatory, Joseph has degraded mentally, spiritually, and physically. He is listless, unmoored, irritable, a burden to his friends, a stranger to his family. He lashes out in a few moments of shocking violence incongruous with his former nature. He takes long, cold, wet walks through the Chicago streets, brooding.

Joseph’s idleness is painfully relatable to anyone who has endured a period of unemployment while ostensibly trying to better themselves. After college, before I secured an internship at Smithsonian Folkways in DC, I lived in Hyde Park for another year, applying to jobs, occasionally seeing some friends, attempting to write and read but mostly failing and watching endless episodes of Stargate SG-1. That winter felt particularly interminable, the long nights frigid and unforgiving. A typical afternoon for Joseph, as the minutes drag and the hours fly, rang true to me:

“By one o’clock the day has changed, has taken on a new kind of restlessness. I make my effort to read but cannot key my mind to the sentences on the page or the references in the words. My mind redoubles its efforts, but thoughts of doubtful relevance are straggling in and out of it, the trivial and the major together. And suddenly I shut it off. It is as vacant as the street. I get up and turn on the radio again. Three o’clock, and nothing has happened to me; three o’clock, and the dark is already setting in; three o’clock, and the postman has bobbed by for the last time and left nothing in my box. I have read the paper and looked into a book, I have had a few random thoughts… and now, like any housewife, I am listening to the radio.”(Dangling Man, 16)

Instead of the radio, I had Netflix. There is a real anguish in an excess of languor, one that is amplified by the realization of the absurdity of it—one should be grateful of the time, of the leisure. Free time is the envy of the overworked. But lack of structure can be its own prison if one lacks the internal resources, the discipline, the “character,” as Joseph puts it, to make one’s own meaning.

In some ways, Dangling Man is reactionary, an indictment of a bohemian lifestyle that Bellow witnessed in his Hyde Park/Partisan Review circles but never fully indulged in. Joseph is a lapsed Communist who makes a scene when he is publicly shunned by one of his former comrades. He is miserable when left to his own devices, self-conscious of his uselessness to society. It’s only in the end, when he is finally drafted by the Army, that Joseph feels a measure of optimism and relief. He will, after a year of dangling, finally be given a noble purpose. Bellow purportedly feared being skewered by the critics for a lack of patriotism, publishing as he did in 1943, but from the vantage of the 21st century, Dangling Man’s conclusions are practically red, white, and blue.

“Hurray for regular hours!

And for the supervision of the spirit!

Long live regimentation!” (Dangling Man, 191)

Initially, I was lukewarm on the format of the novel. There is little plot, and all narration comes in the form of dated diary entries. This felt to me like a cop-out, the choice of an insecure young writer who hasn’t committed to learning how to write and structure a proper novel. In tracking down the influences on Dangling Man, I’ve come to partly forgive this choice, although I think the critique stands. According to Bellow: A Biography by James Atlas, there are two major influences on Bellow’s debut novel: Notes From Underground by Fyodor Dostoevsky and The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge by Rainer Maria Rilke. Notes From Underground was an adolescent favorite of Bellow’s, while Atlas identifies The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge as the most direct inspiration for Dangling Man.

All three books—Notes From Underground, The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge, and Dangling Man4 —take the form of diaries or private writings by men living in boarding houses. Dostoevsky’s Underground Man composes a work that approaches a treatise and toys with the idea of sharing his writing, often addressing an imaginary audience of ‘gentlemen,’ but his musings and recollections are so scathing and self-abasing that it seems inconceivable that such a man would ever assent to making his writing public. Malte Laurids Brigge marks his first entry with a date (11 September, rue Toullier; no year); subsequent entries are not dated. Sporadically, Rilke includes footnotes to indicate that a certain passage is “the draft of a letter,” or a parenthetical was “written in the margin of the manuscript.” Meanwhile, Dangling Man consists of many diary entries of varying length, all of them dated to the day and year.

Underground Mindset

I re-read Notes From Underground before reading Dangling Man to get into the headspace of young, arrogant, precocious Bellow. It was not difficult; I was a similarly afflicted youth. The intensity of adolescence seems so distant to me now, but reading Notes From Underground brought it all rushing back. When I first read Notes From Underground at 14, I was nearing the apex of my angst and youthful pretension. But the profound sense of identification I had with Dostoevsky’s tortured, embittered Underground Man was genuine. As an anxious, depressed teen with intellectual ambitions, I simultaneously thought myself to be superior to my peers and infinitely wretched and contemptible. I felt there was something rotten at my core. I didn’t know how to talk to anyone, or how to be in the world, and I both disdained and envied my schoolmates who seemed to make friends and interact so effortlessly.

“Today it is entirely clear to me that, due to my unbounded vanity and hence demands upon myself, I often looked upon myself with furious dissatisfaction, verging on loathing, and therefore mentally attributed my own feeling to others. For example, I hated my face. [...] Naturally, I detested all my office colleagues, down to the last one, and despised them all, and yet I seemed to fear them too. At times I’d even suddenly decide they were superior to me. In those years my feelings were always shifting suddenly; now I despised people, now set them above myself.” (Notes From Underground, p.42-43)

This attitude was supremely comprehensible to me as a teenager. I experienced endless recursions of self-doubt and loathing. I would think my way into paroxysms of psychic pain so consuming that I felt my only recourse was to seek mind-altering experiences. I came to think of drugs, sex, and other risk-seeking behavior as both an escape hatch from the prison of self and a portal to a more complete understanding of myself. I don’t recommend this path; Hunter S. Thompson said “buy the ticket, take the ride,” but at some point you might want to get off the ride, and it’ll cost you more than the price of admission. Still, I don’t know who I’d be today if I had never bought that ticket.

Notes From Underground isn’t all bitter navel-gazing. There are also some stirring proclamations about human nature and the course of history mixed in with the self-flagellation, especially in the first half of the book. Check out this banger:

“Let us suppose, gentlemen, that man is not stupid. (And really you cannot say he is stupid, if only for the reason that if he is stupid, then who is intelligent?) But even if he isn’t stupid, he is nevertheless monstrously ungrateful! Phenomenally ungrateful! I even think that the best definition of man is: biped, ungrateful. But this isn’t all; this is not yet his principal fault; his chiefest fault is his constant depravity—-constant, from the time of the Universal Deluge to the Schleswig-Holstein period of human destiny. Depravity, and hence lack of good sense. For it has long been known that lack of good sense results from nothing other than depravity.” (Notes From Underground, 28-29)

The tonal resonance between Notes From Underground and Dangling Man is clear. Joseph is descending into a state of bitterness and bile, much like the Underground Man. But Joseph’s mental state is not so purely wretched, and his thoughts are laid out with something less than the brutal, unrelenting honesty found in Dostoevsky, or indeed, in Bellow’s later work. I felt that Bellow was pulling his punches, keeping something hidden in reserve. He was still married to his first wife, Anita, when the book was published. It’s not a flattering portrait of their early marriage, but Bellow hadn’t developed the confidence to take the nuclear option of total self-exposure, yet.

Bellow attempts to engage in some philosophizing near the end of Dangling Man. The entries for February 3 and March 16 take the form of dialogues between Joseph and an entity he calls “The Spirit of Alternatives.” This is a Dostoevskian flourish, but it’s a shallow attempt that flits from topic to topic to comic effect without daring to come to any conclusions. Quite possibly these interludes are lost on me due to my deficiency in German Idealism and Phenomenology and whatever else they touch on, but nonetheless I found them the weakest parts of the novel.

Death and Downward Mobility in Paris

I’ve been unsuccessful in triangulating Bellow’s interest in Brigge; “Rilke” is not mentioned in his published letters, and a Google search reveals only a passing mention of Rilke as an “odd, difficult, idiosyncratic” sort of genius who appealed to a “small public” in a 1976 interview with the New York Times (on the occasion of Bellow’s Nobel Prize in Literature win). Atlas, in his biography of Bellow, confidently asserts that Dangling Man was directly inspired by Brigge, but provides no further elaboration. Perhaps he felt the connection was self-evident. Joseph’s Hyde Park landlady is named Mrs. Briggs, a possible allusion. (If anyone knows of any further writing on how and when Bellow encountered this novel, please let me know in the comments!)

Certainly, the diaristic formats of Rilke’s novel and Dangling Man are similar. Each chronicles a lonely, introspective, intellectual young man surviving in a city. Rilke’s Brigge and Bellow’s Joseph are both 28 years old. Brigge was a sickly child, frequently suffering fevers. Bellow spent six months in the hospital at the age of 8 after developing pneumonia. It’s easy to imagine that Bellow saw himself in Brigge. But the preoccupations of each book are wildly divergent.

The book is based on Rilke’s experience of living alone in Paris in 1902, away from his wife and infant daughter, while he was writing a monograph on the sculptor Rodin. Rilke chronicles a lonely aristocratic childhood in a vanished European world of the 19th century, peopled by ghosts, psychotic mothers, dogs, and servants. Brigge, whose father somehow lost the wealth and property of his youth, now lives in a humble furnished room, with nothing but a library card to distinguish him from the faceless masses of paupers in the streets of Paris. His overriding emotion is fear, and his obsessions are death and the purity of love. But Brigge does not fear death; he fears small and incomprehensible things, and he fears the erasure of crowds in the crush of the city. His anxious scenes of the crowd are superb evocations of the panic one feels when caught in a crowd that one is not part of:

…I felt compelled to go back out into the streets, where a viscous tide of humanity flowed towards me. It was carnival time, and evening, and everyone was at leisure, out and about, rubbing up against each other. And their faces were filled with the light that fell from the stands, and the laughter oozed from their mouths like pus from open wounds. The more impatiently I tried to make my way through, the more they laughed and thronged closer together. Somehow a woman’s shawl got caught on me; I dragged her behind me, and people stopped me and laughed, and I felt I ought to laugh as well but I couldn’t. Someone threw a handful of confetti in my eyes, and it stung like a whip.[…] But although they were standing still while I raced about like a lunatic at the roadside, wherever there were gaps in the crowd, the truth of it was that they were moving and I never budged an inch… I had no time to think about it, I was heavy with perspiration, and a numbing pain was coursing through me, as if something too large were being borne upon my blood, distending the veins wherever it went. And all the while, I felt that the air had long since been exhausted and I was merely breathing in exhalations, which my lungs refused. (Section 18, p.31-32)

Brigge is constitutionally incapable of releasing himself into the crowd. He’s too strange, too uptight, to allow himself to be absorbed into the Dionysian hive mind. The neuroticism of his princely childhood, full of semi-delusional terror, plagues him still as a 28 year old man.

Death, in contrast, is an old friend:

In the old days, people knew (or perhaps had an intuition) that they bore their death within them like the stone within a fruit. Children had a small one within and adults a large one. Women bore theirs in the womb and men theirs in their breast. It was something people quite simply had, and the possession conferred a peculiar dignity, and a tranquil pride. (Section 8, p. 7)

And what a rueful beauty was lent the women at times when they were pregnant and stood, hands involuntarily resting on their large bellies, in which there was a twofold fruit: a child, and a death. Did not the replete, almost nourishing smile on their faces, free of all else, come from their intermittent notion that both were growing? (Section 9, p.11)

The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge was slow going for me, interspersed with pockets of the sublime.

warned me that it’s very much a “poet’s novel,” and I’ve found that to be true. Rilke has a habit of granting agency to inanimate objects in a way that I find irritating, although I’m sure it would be beautiful in verse. I found the footnotes in my Penguin Classics edition indispensable as Brigge relates obscure tales from Danish history—but even with an editor’s assistance I occasionally found my eyes glazing over. Clearly I need to brush up on my Enlightenment-era European history. In spite of the boring bits, I found myself thoroughly charmed by Brigge’s fondness for dogs. He mentions them many times throughout the book, as companions during his lonely boyhood and in an imagined idyllic bourgeois future as a shopkeeper.5If it’s true that Saul Bellow was inspired by Brigge to write Dangling Man, I would judge that Bellow’s aspirations exceeded his abilities. While I enjoyed the wintriness of the latter and appreciated its close attention to the Chicago setting6, Dangling Man fails to achieve the dizzying heights of poetic prose that Rilke churns out without breaking a sweat. It feels like a novel caught between wanting to say something and be exquisite, and ultimately falling short of both goals.

The Woman Problem

I want to linger a moment on the issue of women in Dangling Man. Just a few weeks ago, I strenuously argued that Saul Bellow, the five-time husband and famous womanizer, was not a misogynist. He simply loved women to excess.

But in reading his freshman effort, I’m confronted with some compelling evidence that he may, in fact, have been a bit of a dog. Dangling Man is unique among the three books in that its narrator is married to a woman who is present in the story. This woman supports him financially. Malte Laurids Brigge and the Underground Man are both, apparently, bachelors, each living with only the memory of a woman.

Joseph is married to Iva, whom he met when they were both teenagers. Iva is intelligent, but her misplaced feminine values annoy Joseph. Joseph is cheating on Iva with a woman even less “clever” than she is. He concludes that women are simply constitutionally incapable of pursuing serious intellectual lives without being distracted by frivolous pleasures:

“Iva and I had not been getting along well. I don’t think the fault was entirely hers. I had dominated her for years; she was now capable of rebelling…I did not at first understand the character of her rebellion. Was it possible that she should not want to be guided, formed by me? I expected some opposition. No one, I would have said then, no one came simply and of his own accord, effortlessly, to prize the most truly human traditions, the heavenly cities. You had to be taught to struggle your way toward them. Inclination was not enough. Before you could set your screws revolving, you had to be towed out of the shallows. But it was now evident that Iva did not want to be towed. Those dreams inspired by Burckhardt’s great ladies of the Renaissance and the no less profound Augustan women were in my head, not hers. Eventually I learned that Iva could not live in my infatuations. There are such things as clothes, appearances, furniture, light entertainment, mystery stories, the attractions of fashion magazines, the radio, the enjoyable evening. What could one say to them? Women—thus I reasoned—were not equipped by training to resist such things. You might force them to read Jacob Boehme for ten years without diminishing their appetite for them; you might teach them to admire Walden but never convert them to wearing old clothes.” (Dangling Man, 97-98)

I bristled at this passage. I’m triggered by the idea of being “guided” and “formed” by a “man.”7 But doth the lady protest too much? I, too, am prone to these feminine distractions. If YouTube ever put together a Spotify Wrapped-style summary of how many hours I spent watching video tutorials for applying liquid eyeliner in college instead of reading Walden or Heidegger or whatever, I think I’d die of humiliation. But what I think Bellow gets wrong here is identifying Iva’s resistance to his intellectual guidance as uniquely feminine. Men are just as prone to distraction, but instead of “curtains and jam”8 they have Marvel movies and mistresses.

At least, that’s what I’m telling myself to keep the internalized misogyny at bay. I’m ashamed to admit that, for a long time, I doubted whether women could be serious writers and thinkers. Someday, I’d like to be one.

In Conclusion

Reading Dangling Man alongside Notes From Underground and The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge transformed what began as a straightforward encounter with a slim debut novel into a deeper inquiry into the literature of isolation, introspection, and urban dread. All three narrators, in their different contexts and registers, grapple with the absurdity of consciousness unmoored from structure—be it war, work, history, or society.

In Joseph, I saw the beginnings of Bellow’s later greatness, even as his voice remained undistinguished, his ideas undercooked. But I also saw something familiar: the fear of purposelessness, the temptation to elevate idleness into insight, and the ache of being a self in winter. These books reminded me of my own dangling years, when time felt both heavy and hollow, and I tried to shape myself into someone serious through the rituals of reading and writing. Maybe that’s what these diarists offer us: the strange, cold comfort of knowing that even our most futile flailing has a long and literary pedigree.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing if you haven’t already and leaving a tip via Buy Me A Coffee if you’d like to show your support but don’t want to commit to a paid subscription.

Or an espresso con panna.

Devoted readers know that I recently quit my 9-5. So far I’ve managed to avoid spiraling into a new phase of spiritual disorder; but watch this space.

My husband and I visited Montreal for the eclipse last year and I loved it. I bought my copy of Dangling Man in a used bookstore on Saint-Laurent Boulevard in Montreal.

The working title was Notes of a Dangling Man.

My first friend was a German shepherd named Roxy, so I have a soft spot for weird little kids who like dogs.

Was that cafeteria Joseph visits on 53rd Street THE Valois, established 1921, favorite haunt of Barack Obama and myself?!

For more on my villain origin story and why this triggers me, see this post about Philip Roth and Silver Jews:

I recently read this phrase, intended to be dismissive of women’s interests, in one of the books I’m reading/read. Was it in Dangling Man?? I can’t find it again, but I loved it. So concisely condescending.

Good post. I have most of Bellow's books, which I would pick up when I saw dirt cheap copies. But I have only read Ravelstein, which I liked.

I was in HP a few weeks ago and it was sad to see that Valois, though it survived Covid, only serves breakfast and lunch now. The beef short ribs on Saturday were something I pined for all week. I lived two blocks away for one year, including the months of misery when I worked at the Chicago Mercantile Exchange -- The Merc -- from November 1986 to April 1987 -- a Chicago Winter. I had to get up at 4:00 a.m. to get the 5:18 Illinois Central at 53rd St. to downtown to be on the trading floor at 6:00 a.m. The walk to the train station and the wait on the platform were cold, and I still recall cutting diagonally across a parking lot in full nighttime darkness with no one else afoot. I took a bad spill once, and cut my hand but I got up and kept going to not miss my train, as one does in adulthood. Coming home, despite being desperate for cash, I lacked the willpower to walk past Valois, and I ate there every night. It was the only real meal I ate on any given day. Lunch was out of the question, even leaving the trading floor to urinate was not possible. Breakfast was instant oatmeal, there was no time for anything more complex. When I finally got fired, by a trader who is still a friend, who could no longer afford a clerk who could not do arithmetic quickly and with unerring accuracy, I was feeling very sick. I was going through a full can of extra strength (orange flavor) Sucrets every day, to suppress the incessant sore throat. Upon achieving the blessed state of unemployment, I immediately went to see Dr. Nadler, whom you would have loved. He was from Vienna, and I see he died in 2017 at age 95. He took one look and said I had the worst case of strep throat he'd ever seen. He gave me an antibiotic and said go home and to to bed and don't get up until the throat starts to feel better. The ensuing period of unemployment was as miserable as you describe, anxiety about money making what should have been a gift of hours and days, even in a Chicago Spring, almost unusable.

(I may make a post out of this ...)

UPDATE: Looking at the video, I see he was from Czernowitz. Maybe he studied in Vienna? In any case, I thought there was a Vienna connection.

https://editions.fortunoff.library.yale.edu/essay/hvt-0536#fn-119

My personal project for the last year and a half was reading all of Bellow's novels. (Which also read me to Allan Bloom, who is the subject of his final novel, albeit in disguise...) My thoughts on Dangling Man here: https://menzgeorge.wordpress.com/2023/11/09/the-saul-bellow-read-along-part-1-dangling-man/