Philip K. Dick is Sci-Fi Saul Bellow

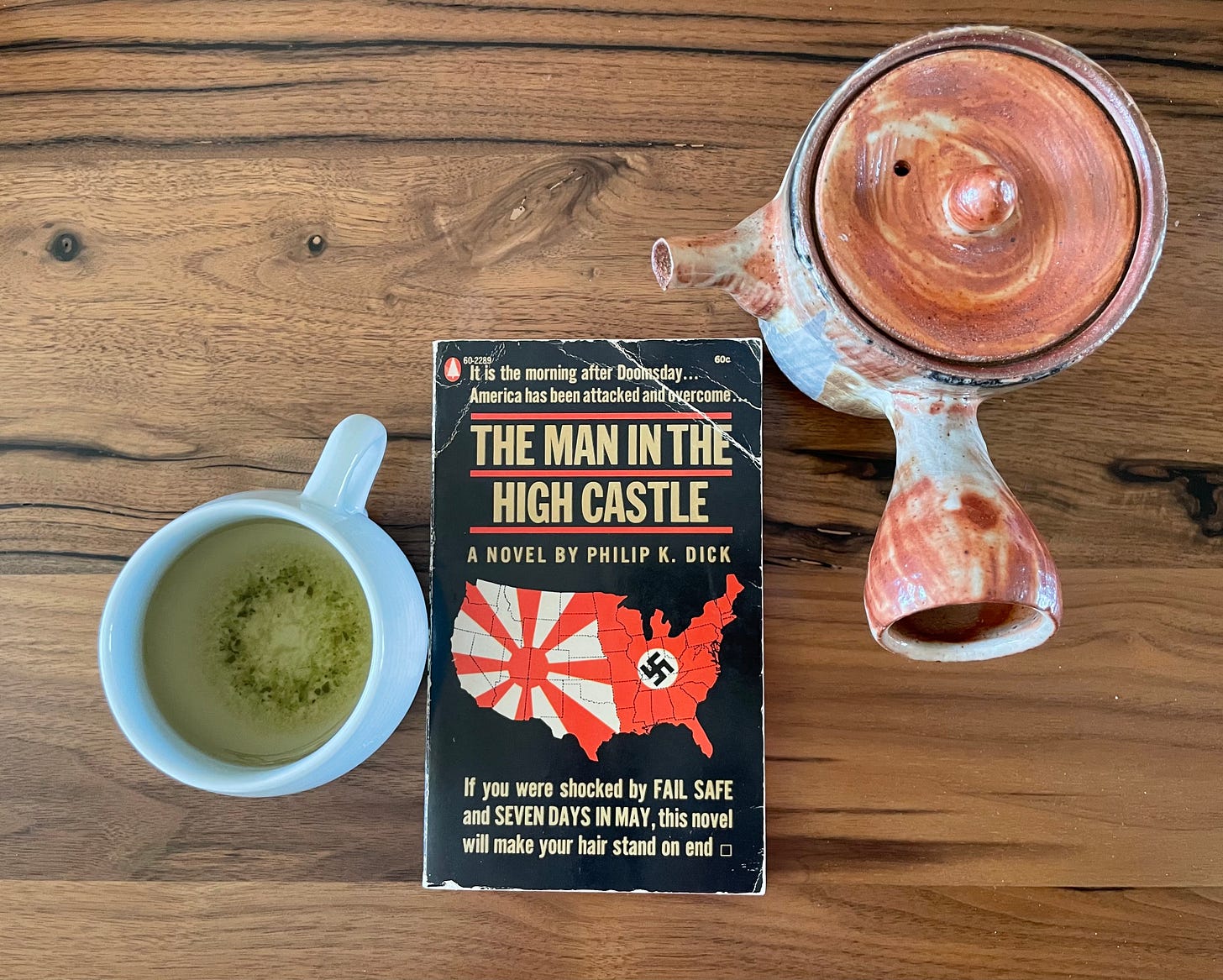

Galactic Pot-Healer (1969) & The Man in the High Castle (1962)

Philip K. Dick is deeply misunderstood in popular culture. He’s often heralded as a prophet, a madman who foresaw the madness of our present world. Or he’s viewed as a trippy weirdo, a conceptual goldmine for stylish thrillers and moody noir. Blame Blade Runner, blame Total Recall. “Based on a story by Philip K. Dick” is a red flag, a red herring, in every case except for the movie A Scanner Darkly (dir. Richard Linklater, 2006). It’s the only adaptation of a PKD story that is faithful to the spirit of the text. I will die on this hill. A Scanner Darkly is one of the greatest film adaptations of any book of all time.

I’ve recently entered something of a personal PKD renaissance in my own life. I first discovered him in my mid-teens (I read Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? after watching Blade Runner for the first time at age 14) and read him voraciously for several years. In the last few months, I read new-to-me Galactic Pot Healer, re-watched The Man in the High Castle TV show, re-read The Man in the High Castle, re-watched A Scanner Darkly, and re-watched Minority Report. (I’ve also recently watched Season 3 of The Bear, featuring television’s most vocal [only?] PKD fan, and have tried to incorporate “you fucking replicant” into my insult repertoire.) I’m struggling to articulate what really lights me up about PKD, and why the prophet/madman branding fails to capture the crux of the attraction for me.

It’s true that some of his worldbuilding rings eerily true in the 21st century—he anticipated the Opioid Crisis in A Scanner Darkly, the plastics apocalypse in Galactic Pot-Healer, and our increasingly fractured relationship to reality in almost everything he ever wrote. And he was mad. Dick believed, in a literal sense, that the world of the early, persecuted Christians still existed, overlaid on the world of SoCal in the 1970s. He spent the last decade of his life receiving messages from God through a pink beam of light. But he wasn’t just a nutty idea generator or a space age, amphetamine-fueled Nostradamus.

Really, Philip K. Dick is science fiction Saul Bellow.

Who am I to expound on the true nature of Philip K. Dick? Allow me to present my credentials.

I’ve read 16 of the 44 novels Dick published, plus uncounted dozens of his 121 short stories. That means I’ve only read a little over a third of his corpus, but it’s still more books than I’ve read by almost any other single author.

I did some quick tallying out of curiosity. The top place goes to Stephen King: I’ve read 19 of his books, which, to fans of the Dark Tower series, is a deeply satisfying number. As previously discussed, I was a huge King fan and I read most of those 19 books before I turned 19. Next is PKD with 16, then Isaac Asimov with ~10, and Vladimir Nabokov picking up fourth place with 9. (I have plans to read Speak, Memory and Mary this year, and no specific plans to read any more Asimov, so this leaderboard is ripe for a shakeup.) I’m sorry to say that I in no way tracked all the books I re-read, so these are imperfect metrics, but I think it’s still fair to say that I indeed qualify as a Philip K. Dick superfan. While not a true PKD scholar, I’d venture to say that I’ve read more PKD and spent more time thinking about PKD than your typical reader.

And one thing I’ve noticed is that, while everyone celebrates his genius as a thinker and inventor of ideas and creator of realities, no one ever talks about his literary quality as a writer.

So: Philip K. Dick is sci-fi Saul Bellow.

What does that mean? I don’t know, but it feels right. Let’s unpack.

First, both men were married five times. I know it’s very chic to separate the art from the artist these days, but these nuptial statistics are not a coincidence irrelevant to the literature they each produced. I have an unscientific theory of the kinds of men who marry multiple times.

1-2 marriages: normal behavior. You get it right the first time–fantastic, ideal, congratulations. Or you get it wrong the first time–hey, you were young and stupid, but you settled down with the right gal in the end. Well done.

3-4 marriages: you are a filthy, depraved old man, trading in each beautiful wife for a younger, hotter model at every opportunity. You will never be content, let alone happy. Women are status symbols to you, not people.

5 marriages: you are a sensitive soul with a tragic flaw; you fall in love too readily; you have a true love of womankind and yet something in you prevents you from loving or receiving love to the fullest from any one woman for your entire lifetime.

In an interview in 2010, Bellow’s fifth wife, Janis, had this to say about her deceased husband:

“He wasn't really a bad boy. He was a serial marrier, but it had to do with a strange desire on his part to be intimate, to have love at the centre of his life. That was part of the daring I saw in him. He was audacious! What would it take to start over again [at that time in your life]? He was hungry in his soul.” [...] “He had a way of being that was total openness, or nothing: you give yourself madly, or why bother? He opened himself up. He had that capacity: to be loved, and to be in love."

Saul Bellow is sometimes uncharitably lumped in with John Updike and Philip Roth, the mid century male novelists David Foster Wallace famously dubbed the Great Male Narcissists, literary Phallocrats obsessed with sex and their own members, and yet strangely incurious about women as people. It’s true that Bellow wrote quite a bit about sex, but his women are fully rendered humans. Bellow was a profoundly sensitive observer of people and especially women. He could be cruel in his depictions, but he was never shallow. For a lengthier discussion of this, see my review of Humboldt’s Gift.

Similarly, Dick’s women are ripe for misinterpretation. He often writes male characters who are divorced or near-divorce, with cruel or distant wives and ex-wives. By nature of the genre, the women of Dick’s novels don’t map as neatly onto ‘reality’ as Bellow’s women do—Bellow was famous for his thinly veiled romans a clef, where minutiae of biography appear barely altered in print. But still, Anne, PKD’s third wife, described being tormented by finding echoes of herself in the women he wrote after their marriage ended.1 And behind Dick’s prose, one feels the pulse of true experience, the push and pull of love and resentment:

His ex-wife, although he hated her for it—and for a lot more—had a quick mind. Even now, a year after their divorce, he still relied on her powerful intellect. It was odd, he had once thought, that you could hate a person and never want to see them again, and yet at the same time seek them out and ask their advice. Irrational. Or, he thought, is it a sort of superrationality? To rise above hate…

Wasn’t it the hate which was irrational? After all, Kate had never done anything to him—nothing except make him excessively aware, intently aware, always aware, of his inability to bring in money. She had taught him to loathe himself, and then, having done that, she had left him.

And he still called her up and asked for her advice. (Galactic Pot-Healer, 13-14)

Galactic Pot-Healer is about an ordinary man, Joe Fernwright, a ceramic pot-fixer by profession, who is recruited by a powerful alien entity to join an inter-galactic team to restore a sunken temple on a distant planet. His alien co-workers are a delightful parade of silly creatures, but there is a deep humanity to the central characters.

The Man in the High Castle portrays a parallel universe in which the Allies lost World War II and America is split between Japanese occupation on the West Coast and Nazi occupation on the East Coast and the South. In Japanese-occupied San Francisco, Jewish metal smith Frank Frink pines after his ex-wife with similarly complex emotions:

Oy vey, he thought, settling back. So she was wrong for me; I know that. I didn’t ask that. Why does the oracle have to remind me? A bad fate for me, to have met her and been in love—be in love—with her.

Juliana—the best-looking woman he had ever married. […] But above and beyond everything else, he had originally been drawn by her screwball expression; for no reason, Juliana greeted strangers with a portentous, nudnik, Mona Lisa smile that hung them up between responses, whether to say hello or not. And she was so attractive that more often than not they did say hello, whereupon Juliana glided by. At first he had thought it was just plain bad eyesight, but finally he had decided that it revealed a deep-dyed otherwise concealed stupidity at her core. And so finally her borderline flicker of greeting to strangers had annoyed him, as had her plantlike, silent, I’m-on-a-mysterious-errand way of coming and going. But even then, toward the end, when they had been fighting so much, he still never saw her as anything but a direct, literal invention of God’s, dropped into his life for reasons he would never know. And on that account—a sort of religious intuition or faith about her—he could not get over having lost her. (The Man in the High Castle, 14-15)

Maybe I expect too little of men, but in my view, such delicate observation of women is in itself an act of love that believes in the full personhood of women. And further, Juliana is not just a distant instrument or vessel for Frank’s longings and spite. Juliana is herself a POV character granted both interiority and action in the otherwise languid plot arc of the book.

Last year, I wrote more in-depth about Now Wait For Last Year (1963), which has a troubled marriage at its emotional core. The conclusions the novel draws are ultimately tragic but surprisingly romantic.

Compare the above passages to our introduction to Denise, the protagonist’s ex-wife in Bellow’s Humboldt’s Gift, with whom he is embroiled in hostile and expensive divorce negotiations:

This woman, the mother of my children, though she made so much trouble for me, often reminded me of something Samuel Johnson had said about pretty ladies: they might be foolish, they might be wicked, but beauty was of itself very estimable. Denise was in this way estimable. She had big violet eyes and a slender nose. Her skin was slightly downy—you could see this down when the light was right. Her hair was piled on top of her head and gave it too much weight. If she hadn’t been beautiful you wouldn’t have noticed the disproportion. The very fact that she wasn’t aware of the top-heavy effect of her coiffure seemed at times a proof that she was a bit nutty. At court, having dragged me here with her suit, she always wanted to be chummy. […]

In these conversations, always somewhat dreamlike, Denise believed that she was concerned, solicitous, even loving. The fact that she had gone into judge’s chambers and dug another legal pit for me was irrelevant. In her view we were like England and France, dear enemies. For her it was a special relationship, permitting intelligent exchanges. […] Denise was pelting me with the ammunition she stored up daily in her mind and heart. Again, however, her information was accurate. (Humboldt’s Gift, 224-225)

Denise is formidable, cold, cruel, and a little pathetic. Bellow excels at these complex portraits of women, and so does Dick. I’m aware that this is a controversial opinion on both counts. If you disagree, I invite you to fight me in the comments section. I may or may not be prepared to defend my assertions.

A non-controversial opinion about Saul Bellow is that he is a keen chronicler of (male) inner worlds, with many long, lush passages depicting the running monologues of thoughtful, intelligent men. Bellow is unquestionably a genius of highly erudite lyrical prose.

So is Philip K. Dick.

On the topic of now-illegal tobacco, Joe Fernwright reflects:

Therefore he returned, then, the cigarettes to his pocket, rubbed his forehead ruthlessly, trying to fathom the craving lodged deep within him, the need which had caused him to break that law several times. What do I really yearn for? He asked himself. That for which oral gratification is a surrogate. Something vast, he decided; he felt the primordial hunger gape, huge-jawed, as if to cannibalize everything around him. To place what was outside inside. (Galactic Pot-Healer 6)

Jesus Christ. 6 pages in and this passage hit me with seismic force. “He felt the primordial hunger gape, huge-jawed”—what a powerful, Bellovian phrase! Perhaps one comes to a PKD book for the interstellar romp, but one stays for the dark human insights.

Later, confronted with the possibility of his imminent mortality during a diving expedition, Joe experiences a chill:

And, thinking it now, he felt the chill of the ocean ease back into its grip around him; the enervating cold plundered his loins, his heart—he felt himself freeze, within, into frightened immobility, like a defenseless minor creature; his fear deprived him of his sense of being human, and of being a man. It was not a man’s fear; it was the fear of a small animal. It shrank him, as if devolving him into ages past; it eradicated the contemporary aspects of his self, his being. God, he thought. I am feeling a fear that is millions of years old. (Galactic Pot-Healer 90)

This paragraph struck me as an extraordinary description of mortal fear, of the reptilian-brain terror that we’ve all felt after a too-close brush with death. This is the description of a writer who is deeply concerned with the aesthetic quality of his writing, not just presenting silly aliens and mind-boggling concepts in the most efficient way possible.

Even the absurd aliens and robots are well-read, cultured beings—as knowledgeable as one of Bellow’s University of Chicago academics.

Rustling its antennae in agitation the quasiarachnid said, “Glimmung resembles Faust in all respects. The Faust, at least, of Goethe, which is the version I adhere to.”

Eerie, Joe thought. A chitinous multi legged quasiarachnid and a large bivalve with pseudopodia arguing about Goethe’s Faust. (Galactic Pot-Healer, 73)

The effect is humorous, but it’s also a flex, in the same way that Bellow’s long, lyrical passages that jump from Plato to Baudelaire to Trotsky are a flex.

In the midst of an exchange between Joe and a robot named Willis about theology, Joe realizes that the robot is paradoxically more attuned to the Christian concept of caritas than his humanoid companion.

Obviously, she did not understand. But, oddly, the robot did. Strange, Joe thought. Why does it understand when she doesn’t? Maybe caritas is a factor of intelligence, he reflected. Maybe we’ve always been wrong; caritas is not a feeling but a high form of cerebral activity, an ability to perceive something in the environment–to notice and, as the robot had put it, to worry. Cognition, he realized; that’s what it is. It isn’t a case of feeling versus thinking: cognition is cognition (Galactic Pot-Healer 87)

On the next page, the robot recites Yeats.

Science fiction as a genre has long attracted renaissance men and autodidacts, but few of them are as devoted and unpretentious as Dick. He engages earnestly with the great ideas of Western (and Eastern, in the case of The Man in the High Castle) civilization in his fiction, rather than simply name-dropping a trail of classical references.

I don’t know if my thesis (PKD = SF Saul Bellow) is defensible in any serious way. Of course, they also have the Chicago connection—PKD was born there in 1928, four years after Bellow moved there from Montreal with his family—but PKD is not a ‘Chicago writer’ the way Bellow obviously is. What I most hope to get across is what fine writing it is. I would call Dick’s body of work uneven in quality: he is guilty of producing some hastily written pulpy slop. I don’t see how you get to 44 novels without a few duds. (For the record, I’d name Dr. Futurity and The Crack in Space as the least memorable of the books I’ve read, with Martian Time-Slip as an honorable mention for being actively unpleasant.)

Yet even with those exceptions, and the alien silliness in a book like Galactic Pot-Healer, it’s clear that Dick always wrote with an orientation towards beauty and depth. The Man in the High Castle is delicately structured and its many characters brought into vital focus.2 He wrote several realist fiction novels that failed to be published in his lifetime, and that focus on the quality of his language is evident in both genres.

I will always proselytize the gospel of Philip K. Dick.

Galactic Pot-Healer: 7.6/10

The Man in the High Castle: 8.5/103

PKD dedicated The Man in the High Castle to Anne, with this savage, backhanded dedication: To my wife Anne, without whose silence this book never would have been written.

Robert Childan, an antiquities dealer who both admires and resents the occupying Japanese, is one of the best-written characters in fiction.

I didn’t write as much about High Castle in this post, since I’ve read it multiple times, but I’ll say that I enjoyed its subtlety more this time around than when I first read it as a teen.

I am reading Ubik as we speak and am blown away by Dick's ability to visualize an alternative temporal reality that speaks to today's political ennui even though it was written in 1969. For someone to do that, they have to be a very special writer with an amazing mind. Like a genius. btw I also like Bellow.

Good post.

Agree about Robert Childan, a great character. I am working from memory, since my copy of the book is elsewhere, but Childan, sweeping in front of his store, thinking about how he hates the Japanese, but his mode of thinking and vocubulary are Japanese! His mind and motives have been colonized, and HE cannot see that but we, the readers can. This is an extraordinary literary feat. I read that book as a teenager, and I saw what PKD was doing then.

Really a pity that the TV show lost its way. A straight, literal depiction of the book would have been better than the mishmash they ended up with. That, or after the first season, let everyone else fade out and make it exclusively about John Smith and Chief Inspector Kido, two good characters played by top notch actors.

Agreed also that PKD's reputation as a sort of madcap fellow who writes about drugs and robots has unfairly ghettoized him. This has unfairly obscured the quality of his writing, which is often excellent, even in terms of prose style, and the quality of his penetration into the human mind and heart, the uniquely decent and charitable way he sees his characters and the world, and his prescience about how timeless human nature would respond to radical changes in technology.

Martian Time Slip, which I read over forty years ago, leaves behind a bleak, squalid feel. But still, Can-D and the Perky Pat set, stick with you. It is set in a housing project, after all. It is sort midcentury kitchen sink realism, with mental illness and drug abuse, except on Mars.

As to Bellow, I've only read Ravelstein, which I enjoyed. I started The Dean's December and didn't like it. Given sufficient longevity, I may give him another chance.

And Norman Mailer was married six times. Your typology seems to fit him. I will read more Mailer before I get to Bellow again.