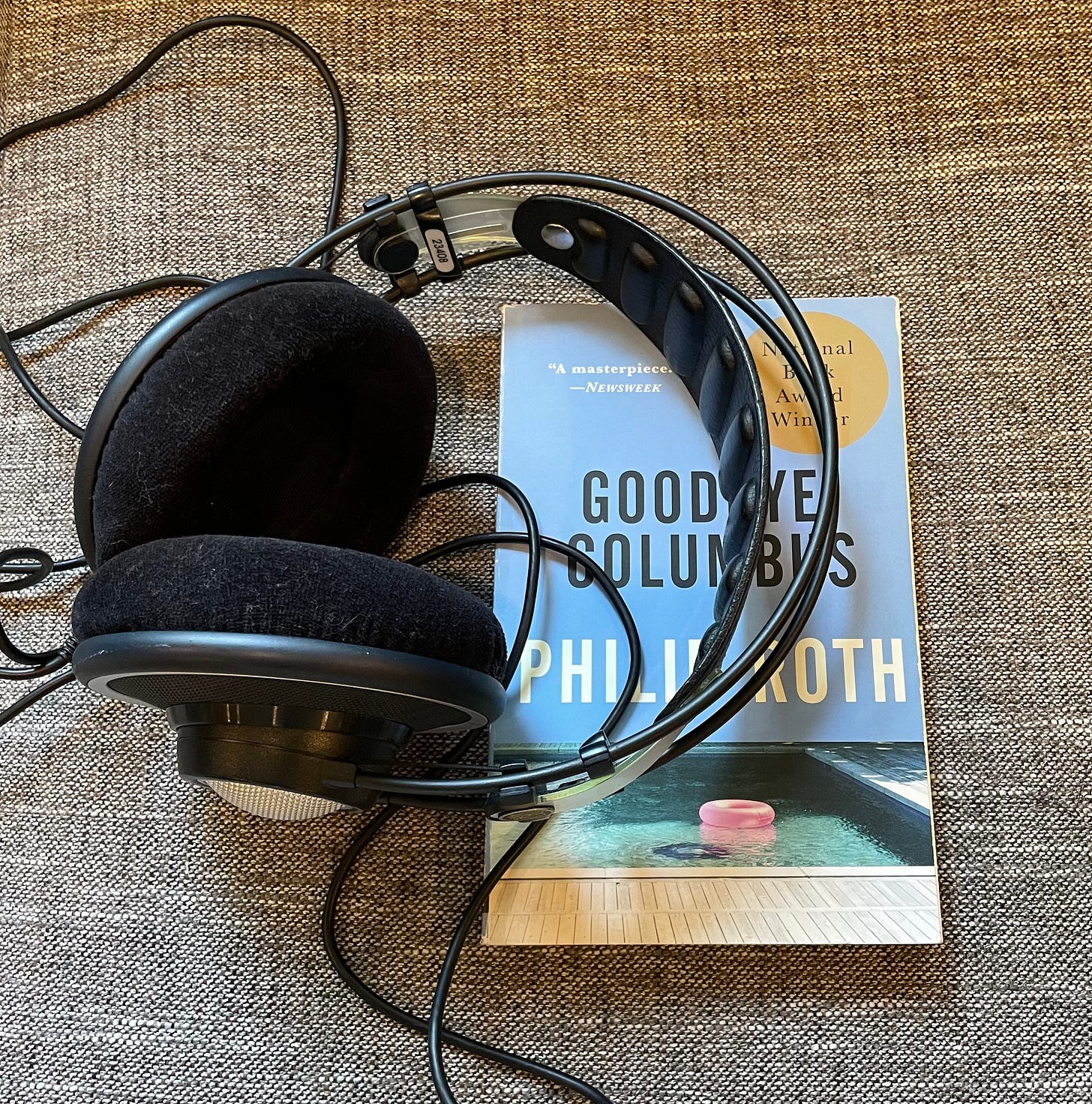

We spent the rest of the afternoon in the water. There were eight of those long lines painted down the length of the pool and by the end of the day I think we had parked for a while in every lane, close enough to the dark stripes to reach out and touch them. We came back to the chairs now and then and sang hesitant, clever, nervous, gentle dithyrambs about how we were beginning to feel towards one another. Actually we did not have the feelings we said we had until we spoke them— at least I didn’t; to phrase them was to invent them and own them. We whipped our strangeness and newness into a froth that resembled love, and we dared not play too long with it, talk too much of it, or it would flatten and fizzle away.

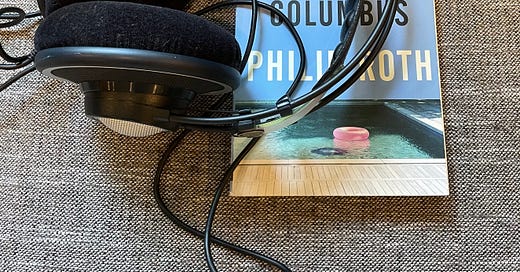

(Goodbye, Columbus, p18-19)

I don’t remember how I was first introduced to Silver Jews, but I expect another WHPK DJ played them for me during my first year of college. Rachel? Was it you? I heard “Random Rules,” the opening track to their 1998 album American Water and was instantly hooked on the bemused drawl, the dry wit, the vivid imagery, and the winking depth of feeling. The summer before my senior year, I interned at Drag City Records and even got to meet David Berman, the genius behind Silver Jews.

After college, when I finally broke up with my abusive ex, I spent an entire year without really listening to music. I went from listening to music and making playlists on a near-constant basis to only occasionally charging my iPod. Silver Jews were one of the few bands I could bear to listen to; we had shared so much music together, but he hated Silver Jews for some reason (possibly antisemitism). I turned to their music because, unlike most of the music I love, Silver Jews didn’t make me think of him. It was a small scrap of evidence that, despite being subsumed by the force of his personality for six years, it was possible for me to have my own taste, my own thoughts and beliefs and preferences. (I was 17 when we met; he was 38.) Until then, I didn’t truly believe that I possessed an inner life independent from him and what he told me to do and think and like. It was a form of aesthetic and intellectual bondage.

Making new connections between the media I consume and repairing my relationship to music, literature, and cinema has been the greatest project and pleasure of the last several years. Now, since recently reading Goodbye, Columbus, the Silver Jews song “Blue Arrangements” invariably evokes for me the titular story in that collection. The first time the song, from the album American Water, came on after I read Goodbye, Columbus, I stopped dead, feeling that I’d never truly listened to the lyrics before:

I see you gracefully swimming with the country club women

In the Greenwood South Side Society Pool

I love your amethyst eyes and your Protestant thighs

You’re a shimmering, socialite Jew

(the internet says that last word is actually ‘jewel,’ which makes sense with ‘shimmering,’ but I always heard ‘Jew.’)

From the Carbon Dioxide Riding Academy

To the children's crusade marching through the downtown

Well, I think I'd die, see, if you just said hi to me

When something breaks it makes a beautiful sound

Sometimes I feel like I'm watching the world

And the world isn't watching me back

But when I see you, I'm in it too

The waves come in and the waves go back

Why, that’s Goodbye, Columbus! Meeting at the country club pool, a seemingly unattainable Jewess of a different class than the alienated young narrator— I was struck by the parallels and I can’t unhear them. I did some light Googling to see if anyone has made this connection before and I didn’t find anything that connected the two works. If anyone has done a deeper dive into David Berman and can find an interview or something where he talks about Philip Roth’s influence on his music, I’d be eternally grateful if you’d share that with me. Other than the vibes matching up in my head, I have no evidence that “Blue Arrangements” has anything to do with Goodbye, Columbus. But at the same time, I’d be extremely fucking surprised if David Berman never read Goodbye, Columbus. Wouldn’t you?

But let’s rewind a minute. Goodbye, Columbus is the first book by Philip Roth, one of the quintessential Jewish American writers of the 20th Century. It’s only the second Roth book I’ve read, after The Plot Against America (2004). It’s a collection of short stories. The titular novella concerns a summer fling between 23-year-old working class Newark boy, Neil Krugman, and monied, myopic, nose-jobbed Brenda Patimkin, a coed from a wealthy suburb. Brenda asks Neil to hold her glasses while she dives into the Green Lane Country Club Pool, where Neil is certainly not a member.

So begins an intense romance. Wrong-side-of-the-tracks Neil is a sympathetic but flawed Everyman. The way he fumbles the relationship is rendered in excruciating detail. He wants to do and say the right things but he finds himself saying the wrong thing time after time, drawn to picking fights and doubling down, a painfully familiar dynamic. I, too, was once 23; my foot was never far from my mouth.

This culminates in a truly maddening confrontation that begins with Neil deciding to ask Brenda to marry him and then proceeding to nag her about a sensitive topic instead of proposing. Young, stupid Neil can’t keep his stupid mouth shut and just comfort Brenda in her hour of need. Instead, he piles on and drives her away.

This scene, in my head-canon, maps onto this verse of “Blue Arrangements”:

The room is dark and heavy with what I want to say

I see murals in the radio static and on your blue, blue jeans

What would you say if I asked you to run away?

It's been done so many times I hardly know what it means

It’s an absorbing and convincing story that kept me up past my bedtime a couple of nights in a row. I found the entire collection highly readable, although the prose was not particularly beautiful or stylistically interesting. The stakes are subtle but Roth imbues them with the urgency and drama of youth. There’s an odd sub-plot with a young black boy who loves Gaugin at the library where Neil works, which seems to exist to allow Roth to make a progressive case for his protagonist.

Even though I’m reminded of “Goodbye, Columbus” every time I listen to “Blue Arrangements,” the story from this collection that I found most thought-provoking and enduring was actually the final story, “Eli, the Fanatic.” In this story, a sleepy suburb with a small and prosperous Jewish population becomes the unwilling host to a new group of Jews: Holocaust survivors, most of them orphaned children. The newcomers are Orthodox, visibly observant Jews who cause a stir in the town, generating fear amongst the other Jews in town. They establish a yeshiva in the Anglo enclave, so the Jews of Woodenton launch an intervention. The Gentiles tolerate their assimilationist Jewish neighbors well enough, since the town was recently un-restricted during the war, but the Jews fear that their patience would wear thin if the newcomers were allowed to walk around looking so conspicuously Jewy. Lawyer Eli Peck, one of the suburbanites, is dispatched to negotiate with the headmaster and convey the townspeople’s outrage, which is focused on the headmaster’s associate’s traditional Orthodox garb. Eli offers the man a change of clothes.

Over the last few years, I’ve developed a fascination with intra-group dynamics and the divisions caused by subsequent waves of migration, particularly as applied to American Jews and Asian Americans. For Asian Americans, Jay Caspian Kang’s book The Loneliest Americans provides an engaging treatment of this topic and I highly recommend it. Mainstream America loves to regard its minorities as monoliths, but our demographic categories hide tremendous diversity of culture and experience.

Who is the quintessential American Jew? Is it the German Jew who migrated from Alsace-Lorraine to Cincinnati and joined a prosperous, secular community in the mid 19th century? Or the impoverished Ukrainian Jew who fled pogroms and landed in Brooklyn in the early 20th century? Or the Polish Jew who survived the Holocaust and ended up in Chicago during the exodus from Europe after the war? Or the second-generation Israeli Mizrahi who starts an academic career in Los Angeles after the Yom Kippur War? And how do all these populations feel about each other? This is the problem space that “Eli, the Fanatic” concerns itself with.

In one letter to the headmaster of the yeshiva, Eli suggests that, had European Jewry been more inclined to compromise with their Gentile neighbors and become more modern, as the Jews of Woodenton had, maybe the Holocaust could not have happened. In other words, the religious fanatics were responsible for their own persecution. Eli becomes obsessed with the yeshiva and with the man in the black suit. The boundaries between ‘us’ and ‘them’ begin to blur as the story progresses, until finally Eli finds himself confused about his identity in a very fundamental sense.

“Eli, the Fanatic” indicts the secular, modern American Jew; it indicts me. Its absurd conclusion offers no solution or consolation. And that is a very Silver Jews-y move, to make one laugh at the edge of despair.

I’m going to try out ratings. Disclaimer: they are essentially arbitrary, and I reserve the right to withhold a rating for books by living authors because I’m not here to make enemies or bum anyone out.

Goodbye, Columbus by Philip Roth: 6.8/10

Enjoyed this, thanks for sharing