He sat back in the drive-hammock, staring at black view screens dead to hyperspace. He was, he realized, bypassing in seconds the immense void through which the Star Ships had crept laboriously at a few thousand miles a second for a handful of centuries. Despite stirrings of an excitement that he refused to acknowledge, he still saw himself—a potential Galactic Anthropologist—on his way to track down a minute, trivial incident pertaining to a cultural dead end. (p. 16)

I have a soft spot for a certain kind of masculine hubris, the kind that believes it can make sense of modernity with a sufficiently clever heuristic or end war with a well-constructed grammar. It’s why I love the Great Books and Robert Maynard Hutchins’s attempt to build a better citizen through pedagogy; why I respond to the ambition and folly of Schliemann’s search for Troy on an aesthetic level; why I’m so charmed by the earnestness of Esperanto. There’s something about that pre-WWII optimistic spirit that animates each of these projects that makes me feel glad to be alive. It’s exhilarating to imagine a time before the emasculating bureaucracy of academia congealed into the suffocating feminized miasma of marginal advances and politically correct dinner party culture of the late 20th century and today.

Never mind the destruction that gentlemen-scholars wrought upon priceless archaeological sites! Never mind the casual scientific racism of caliper-wielding eggheads! Never mind all the Great Men who conscripted their wives into secretarial service while they collected medals and awards! Ah, fuck, my internalized white supremacist misogyny is showing again. I can’t help it; I just admire the hell out of all that proud, optimistic bullshit, in spite of (or even because of?) its many pitfalls.

The same boldness of spirit animated the study of ethnomusicology in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Imagine: by crafting a scientific taxonomy of sound, one could come to understand all cultures of all the savage peoples. Alan Lomax could save Appalachia and the Mississippi Delta in the trunk of his car. It is a stirring project.

When I was a rock format DJ with a 4-6am radio show at 88.5fm WHPK (“the Pride of the South Side”), I slowly veered away from playing mostly hardcore punk and began exploring the sizable but largely neglected Folk section of the LP library. The Folk section could only be reached by dragging the rickety ladder all the way around from where it was usually parked in the Rock section to the precarious strip of real estate over the sound booth window, next to the ventilation shaft, and ascending all the way up, near the ceiling. I sometimes wondered, if I fell and broke my neck at 4:30am on a Wednesday, how long it would take before someone noticed the dead air and came to check on me.

My favorite finds were anthologies of pre-war amateur recordings (usually sourced from old 78s) compiled by white men in New York. The voices—raw, powerful, convicted, haunted—bore a hole right through me. These records were voyeuristic, splendid. Their liner notes were problematic and confident. Early Folkways records particularly excelled in these contradictions. It was a heady time of discovery for me.

After college, I spent a year as an intern for Smithsonian Folkways Recordings, the entity that humble Folkways morphed into after the death of Moses Asch in 1986. The official nonprofit record label of the Smithsonian Institution, Smithsonian Folkways matured into an organization that prized its own history but sought to release more responsible scholarship into the world. It was a lovely place to intern, full of well-meaning modern musicologists and banjo-playing archivists. Everyone had a Masters degree. But it did not think it could understand all of human culture through a single lens. It lacked the hubris that I find beautiful.

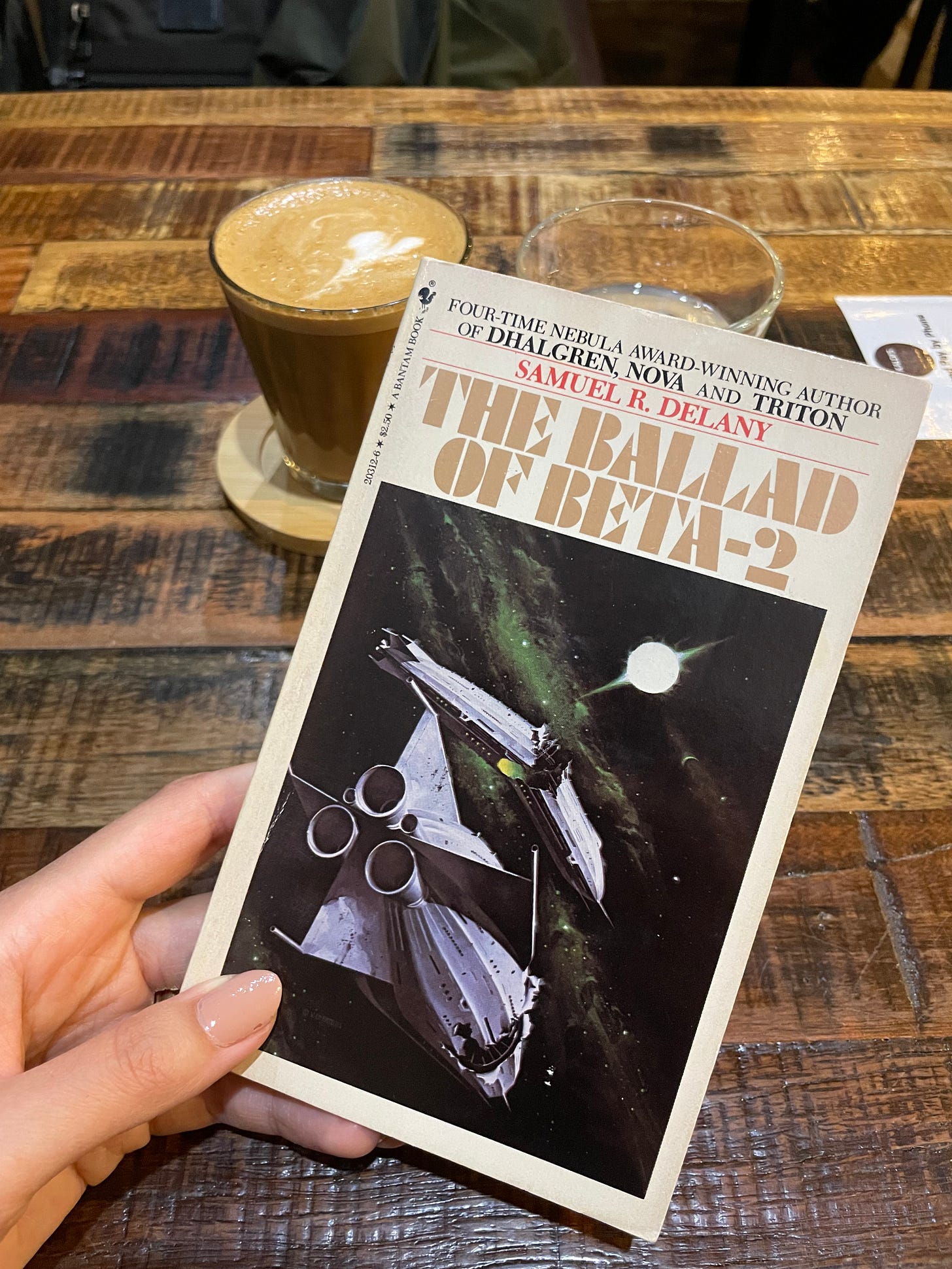

This is all to explain what I found so charming about The Ballad of Beta-2 by Samuel Delany. Far from the badass space captain action of Babel-17, which I reviewed previously, this slim novel features a snobby, know-it-all anthropology student on a field trip as its hero. Specifically, Joneny’s field is Galactic Anthropology, and he is dispatched by his professor on what he considers to be a snipe hunt to the domain of the Star Folk, a branch of humanity that left Earth in century ships before the discovery of faster-than-light travel. Over the millennia, locked in their slow ships, the Star Folk devolved into strange, subhuman creatures, while, unknown to them, humanity learned to manipulate time and traverse vast distances instantly. The rest of the galaxy, now populated by civilized humans, dismissed the Star Folk as a cultural backwater. The Star Folk held strange, incomprehensible beliefs and superstitions, as evidenced by a handful of their recorded songs and ballads—considered by Galactic Anthropologists to be primitive, inbred drivel.

Joneny’s research topic is the Ballad of Beta-2, the lens through which he discovers some shocking historical truths about the Star Folk’s long voyage. The lyrics are initially nonsensical, but as Joneny makes his way through the captain’s logs on the abandoned ships, he gradually begins to understand the references and metaphors in the song.

I’m struggling to think of any other sci-fi story in which a folk song plays such a key role. I was delighted by the idea of far-future ethnomusicologists poring over field recordings and dismissing an entire space-faring race of humans as infertile academic ground. I also adored the premise of a subset of humanity setting out on a centuries-long journey, then being leapfrogged and forgotten after a breakthrough in engine technology. It’s similar to an idea I’ve played around with in my own writing.

Ultimately, the setup is the most enjoyable part of The Ballad of Beta-2. The book is slight, at 115 pages—blink and you could miss it. Delany didn’t so much write a novel as he did string together a few cool ideas and a series of historical journal entries. It’s a fun read, but in my humble opinion, the premise deserves a better story. But maybe that’s in keeping with this theme of careless, bold masculinity I started with: Delany came up with an idea so potent, he didn’t need to write it all out for us, the readers. You fill in the blanks, he seems to say.

Or maybe not, but I’ve written myself into a corner with this hubris thing, and I have to end the review somehow, right?

I love this one Lillian!