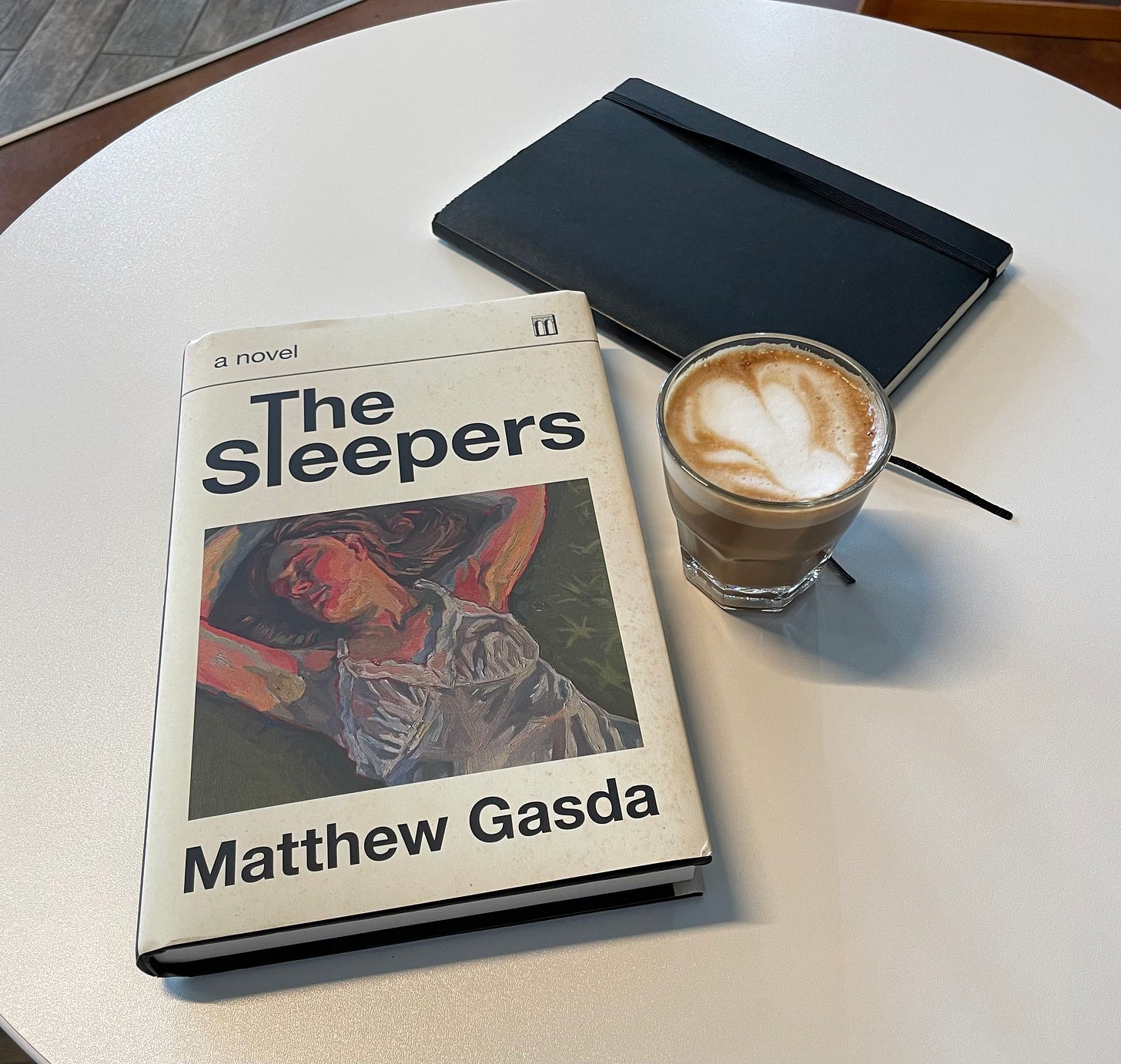

In a first for the Lillian Review of Books, today we are reviewing a buzzy new release, The Sleepers by Matthew Gasda, set to be published on May 6, 2025. I was surprised and flattered to receive the request from Gasda, who at least tactfully claimed to be familiar with my approach to reviewing books (mostly old, mostly Jewish books and/or sci-fi). It’s the first time that I’ve been sent a book for free before its publication date. In spite of my susceptibility to flattery, I’ve done my best to read The Sleepers neutrally and give it the consideration it deserves, and no more.

Let me be upfront with my biases.

This is a New York book. I grew up in Chicago and live in DC; New York chauvinism annoys me. I resent knowing the cultural differences between Greenpoint and Williamsburg, and I resent novels that use these geographic markers as shorthand for character development.

Look, I grew up enamored with the New York of the 1950s–70s as much as anyone. The Beats, Greenwich Village, CBGBs, Max’s Kansas City—any young person who loves music and literature finds themselves drawn to New York City as an idea. But that New York doesn’t exist anymore, and living there in 2025 doesn’t make you better than everyone. Put your novel somewhere more interesting. I’d much rather read about the scene in Milwaukee or Cincinnati or Frederick, Maryland.

I don’t read much contemporary realist fiction. I’m not sure if it’s possible to make the 21st century condition compelling in fiction. Too much of our lives is mediated by technology to make a faithful recreation of modern life artful. I read enough text messages in my own dumb life; I don’t want to read your fictional text messages in your “internet novel.” Maybe this will change in 20 years when we’re all Neuralinking each other psychic GIFs all day and iMessage becomes a nostalgia object.

In spite of my aesthetic hostility to this form of storytelling, I did find Gasda’s description of the screen-time time-warp compelling:

Time escaped in strange ways, excusing itself like a guest at a party, never really saying goodbye, shutting the door before he could say goodnight; in the hyper-fragmented time of the screen, time was itself a kind of ghost: a hallucination in which you sense that your material, embodied life has continued on without you. (86)

A bias in the book’s favor:

I could see myself and my peers in the characters. I have an innate affinity for Gasda’s cast of characters, who are mostly selfish, left/liberal Millennials educated at elite universities. The year is 2016; the election looms. Dan is a late-30s white man (non-Jewish: we are introduced to his uncircumcised cock before we meet the man himself), a nominally Marxist assistant professor of English literature and think piece author. Dan’s girlfriend Mariko is 32, half Japanese, half German American, an aspiring actress (and server). Eliza, Dan’s former student who seduces him for sport, is 21, half Jewish, mentally unstable.

In 2016, I was Eliza’s age, a recent college grad, mentally unstable. It was my dangling year. I didn’t seduce any of my professors, but I was in an abusive relationship with a man 21 years my senior and Eliza’s destructive behavior is totally legible to me. Now, I’m close in age to Mariko, whose anxieties around aging and her appearance are, unfortunately, familiar. As a half Korean, half Jewish woman, I’m always excited (and a little apprehensive) to see hapa characters in fiction.

The novel unfolds over the course of a few days in September 2016 as the unhappy couple, Dan (“the professor”) and Mariko (“the actress”), spiral into separate self-destructive infidelities, while Mariko’s sister Akari crashes at their claustrophobic Brooklyn apartment. At the end of the novel, we get a couple of vignettes to update us on how the characters deal with the consequences of their actions.

I finished the book, which is 273 pages long, in three days. That’s unusual for me. I’m usually reading anywhere from 5–10 books concurrently; I start and stop and restart books all the time. Breezing straight through one book in under a week is rare. Because these characters all felt like people I kind of know, I felt compelled to keep reading. It felt like reading juicy gossip about people in your friend group that you secretly think are the worst.

Style and Substance

Gasda does an enormous amount of telling, as opposed to showing. Each chapter follows the perspective of a different character. Some characters—Xavier, Suzanne—only get one chapter each. The others we revisit throughout the book. The narration is something I’d call close third person omniscient— meaning that we are privy not only to the thoughts of that chapter’s POV character, but also of the subconscious motivations that give rise to those thoughts, the personal histories and psychosexual drives that they can only dimly sense. Gasda does not hint at these dark forces or force the reader to piece them together on his own. He draws the subtext into the light, squirming on a pin, and neatly labels it with clinical detachment.

Mariko had never really learned how to fuck: how to abandon all the higher, critical, self-aware functions of consciousness. She’d only ever had the kind of sex that was about other people feeling good about themselves, the kind of sex that people had out of secret contempt. Some part of her clung to control, to pseudo-rationality, to convention, and structure. Her relationship was designed to keep chaos out—and, in that sense, it served its function very well. (31)

Or:

Women were expected to envelop their bodies in shame. They were expected to simultaneously represent the dual ideals of dewy fuckability and maternal stability. Implicit in her upbringing was the notion that she should be well-groomed, clean, a machine for sexual-pleasure and childbearing. (54)

At first, given our literary culture’s obsession with showing not telling, I took this for an error. It was disorienting for the first two chapters. Gradually, I acclimated and came to understand it as a style. This is the first quality I came to admire about The Sleepers. I’m still not sure that I like this style, its psychoanalytic baldness, but I appreciate its distinctiveness and the boldness with which it was pursued.

This style allows for intriguing possibilities. Gasda has broken the contract between author and reader, the one that we signed in 10th grade English class when we learned that literature is meant to illuminate universal human truths through metaphor and so on, which must be deciphered by the attentive reader. This is what reading is: the uncovering of subtext and implication. Gasda explodes this by serving all the subtext upfront.

What this could do is create space for the reader to work in a different way, to interact with the novel differently than he has been trained to do. I’m not sure that The Sleepers makes good on this promise. Ultimately, I found myself disappointed that the book did not ask more of me. I did not feel challenged or enlarged by the book.

Beauty and Chemistry

I prize beautiful, surprising lyricism in fiction; overly sparse prose bores me. The Sleepers is generally reserved in style, but it contains enough beautiful sentences to serve as a counterweight to the deliberately awkward, unartful dialogue and embarrassing sexts and texts and Facebook chat logs that comprise much of the communication between characters. See, for example:

Across what was left of the waterfront, Manhattan leapt and licked at the sky, like a Van Gogh cypress, or a city in the Bible: hallucinatory and raw. (28)

and

Dan was circumscribed, bound by certain rules: fixed into place. A dying sun in a Ptolemaic universe. (71)

Gorgeous.

Gasda is strongest when he writes about the dynamics of attraction, desire, contempt, arousal, and repulsion. He’s an acute observer of human behavior, and I frequently found myself caught up in these passages.

Dan and Eliza:

He wanted to touch her knee, her thighs; he was obsessed by her skin. He was loving making her laugh; he loved laughing with her. What was happening? He hadn’t done this in years. He hadn’t been on a date in years.

He traced the top of her kneecap with his right hand; he couldn’t help it. With her left hand, she gripped his palm. The little subcurrents of potential energy circulating back and forth between them felt amazing. (103)

Mariko and Xavier:

A charge passed between them. He started to unzip her sundress; she opened her legs slightly; she was breathing heavily.

Then she pushed him away.

She looked at him: he was so old; he carried the stench of death. It would spread to her.

Vampire. (178)

Everyone Sucks Here

The Sleepers belongs to an emerging cancellation-core genre: the movie Tar and the TV show The Chair come to mind. (It would probably be helpful to have read The Human Stain by Philip Roth, but I haven’t.) More broadly, it’s about people who are too weak to resist their desires—a conflict that drives most art of the 20th century. It’s a #MeToo book, but only glancingly. We don’t witness the cancellation, only the build-up and, to some degree, the aftermath.

Perhaps there’s some bravery in depicting Eliza, the young former student, as having a turbulent sort of confidence and agency in initiating the encounter with Dan. But Dan is too pathetic to hold our respect. Mariko is hypocritical, repressed, and cruel. Xavier is pompous and smug. Akari is an irresponsible brat. If the book were an Am I the Asshole thread on Reddit, the verdict would be: Everyone Sucks Here.

Much has been made of Gasda’s Dimes Square roots, supposedly anti-woke allies, and the problematic anti-vax books produced by his publisher’s parent company, Skyhorse Publishing. I’m not really interested in parsing the author’s politics or punishing him for being two degrees removed from RFK Jr. propaganda. I think my only critique along those lines is that Gasda has taken the easy way out by making every character so unappealing. There’s no positive vision for how a person should be.

Then again, a novel doesn’t need to give me that.

A Note About Hapas

As a half Korean, half Jewish woman who is married to a white (non-Jewish) man, my interest was piqued by the potential for a sensitive exploration of Mariko’s hapa psyche. So much of the book is concerned with the minute ways that the characters sense and respond to each other, often misunderstanding. But Mariko’s ethnicity only surfaces briefly a couple of times.

It occurred to her that white men, academics, who had rejected patriarchy in their published work, often courted Asian women in order to regain access to the very object they had theoretically rejected: a submissive female body.

Her sister had subverted this stereotype, but Mariko hadn’t; she had cultivated it precisely because it granted her a secure basis for erotic power. (44)

This is an incisive observation, and I was hoping for more along these lines. Mariko is keenly aware of her changing, aging body, but she doesn’t do much further reflecting on her ethnic ambiguity (she is said to more closely resemble her German American father than her Japanese American mother), the relationship between her Asian heritage, her acting career, and her aging process, or how men perceive her as an exoticized object; I find this omission improbable.

Similarly, we don’t get any reflection from Dan on Mariko’s ethnicity. He seems drawn to Eliza’s otherness when he guesses that she is Latina, but the book fails to explore more deeply the interplay of his racial and sexual preferences. This feels like a missed opportunity, given the rising prevalence of Asian–white romantic pairings, especially in elite circles.

If more was not to be made of these half Asian characters, why name them Mariko and Akari? Why mark them so conspicuously as Japanese when most half-Asian Americans are more likely to be named Mary and Annie? And why make them German and Japanese—the most imperialist hapa combo?

A Place in the Canon?

I warned Matthew when he messaged me about reviewing his novel that I don’t read much contemporary fiction and would be comparing him to the likes of Saul Bellow and Rainer Maria Rilke—whom he then affirmed were two of his favorite writers. I think Gasda wants to be judged against the Canon, not against his contemporaries. The jacket copy proclaims: A Contemporary Tragedy in a Classic Style. But I don’t see either Saul Bellow or Rilke in this book. It has none of Bellow’s humor and little of his erudition or Rilke’s sublime lyricism.

The most proximate analogue that comes to my mind is Joseph Heller’s Good As Gold, a comic novel about a horndog English professor who bullshits his way into the Washington DC halls of power–almost. I shared my frustrations with the book in this review. The Sleepers is not funny, although its characters are often clownish. It’s a better book than Good As Gold, while performing a similar function (in a minor key): excavating the moral decay of a generation of pseudo-intellectuals.

Another comparable title that comes to mind is Indignation (2008) by Philip Roth. It’s a compelling, if ultimately forgettable, snapshot of the psychosexual dynamics on a Midwest college campus during the Korean War. The sex scenes are great fun to read. Indignation evokes the uncertainty and anxiety and joy of being young and stupid in a threatening historical context.

The Sleepers functions in a similar way. Gasda wants the world to know that Millennials, unlike Gen Z, fuck. There’s an enormous amount of fucking, and almost-fucking, in this novel. It’s messy, sweaty, embarrassing sex, but it’s definitely of the fun Philip Roth flavor, as opposed to the strange and off-putting1 Bellow kind of sex writing. The characters feel like archetypes, or subjects of an anthropological field report. If someone wanted to know what it felt like to be a leftist Millennial in 2016, this book would be a good place to start.

Previously, I’ve decreed that Philip K. Dick is sci-fi Saul Bellow. Today, I pronounce that Matthew Gasda is not Millennial Saul Bellow.

But he’s got a shot at being my generation’s Philip Roth. I’m glad I read The Sleepers. I’ll continue to follow his work with interest.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider hitting the like button, subscribing if you haven’t already, and leaving a tip via Buy Me A Coffee if you’d like to show your support but don’t want to commit to a paid subscription. Thank you for reading!

But ultimately much more interesting!

I haven't read the book, but the review was well- written and entertaining. Bravo.

It definitely would not help to have read The Human Stain because it is a terrible book, actually one of Roth's worst.

Thanks for this fairly even-handed review; I have two quibbles with it that maybe are just my own little pricklinesses of the same kind they observe. You complain about NY books, and resenting knowing the cultural differences between Greenpoint and Williamsburg (which is a funny line) and then insist books would be better to be set in more "interesting" places. But to set a book in any other place as well would require just the kind of intricate and intimate scene-setting about that place that you resent about NY novels. Personally even before I lived there, and certainly since, I have never resented NY settings. I also don't resent detailed LA settings, or San Francisco, or Glasgow, London, St. Petersburg, or Montreal (or D.C., clears throat). It isn't inherent to fiction that it have a localized sense of place but certain stories work best with that grounding, and certainly it can be great about rural places too (see Chris Offutt or, my God, Faulkner). I see comments like that and I a roll my eyes at the performative provincialism that wants to shout its credibility as repping for somewhere OTHER than the center. Please give Balzac's Lost Illusions a try and see if it clarifies why this stance is perfectly fruitful aesthetically but extremely tedious both on Substack and generally. You are a smart, thoughtful, and noninstitutional reader/reviewer and it sucks to see reflexive parochialism mar a review.

Secondarily, I note that you admit not reading much contemporary fiction but I gotta tell you, the "telling over showing" is real and standard and commonplace. It's valid if it works, it can weigh down when it doesn't. It is very European in some ways, except European writers are more subtle about it, or at least what it is doing. See Soldiers of Salamis by Javier Cercas or The Postcard by Anne Berest (admittedly also autofiction so somewhat aside of my point) for examples that to my mind, work, or see Paul Auster's Book of Illusions or Leviathan for an American albeit heavily indebted to Europeans who makes it work. Also recall Victorians like Dickens and Collins. Even our beloved PKD does it, albeit most obviously when he was working under a deadline and produced subpar work. I guess my peeve here isn't so much that you are "wrong" for noting this, as that the "show don't tell dynamic" is both highly cliche and not really all that relevant even when it was common, because it is the type of "rule" most honored in the breach.

I apologize; I'm writing fast because i have paying work to get back to, and i realize without rereading that this is a bit lecture-y. Please accept my sincere assurance that it was not so intended and my compliments for writing the review that prompted this; it's always a pleasure to read your thoughts on books. Sooner or later I will get back to Martian Time-Slip and update you on whether it has become unreadable to me as to you. Cheers.