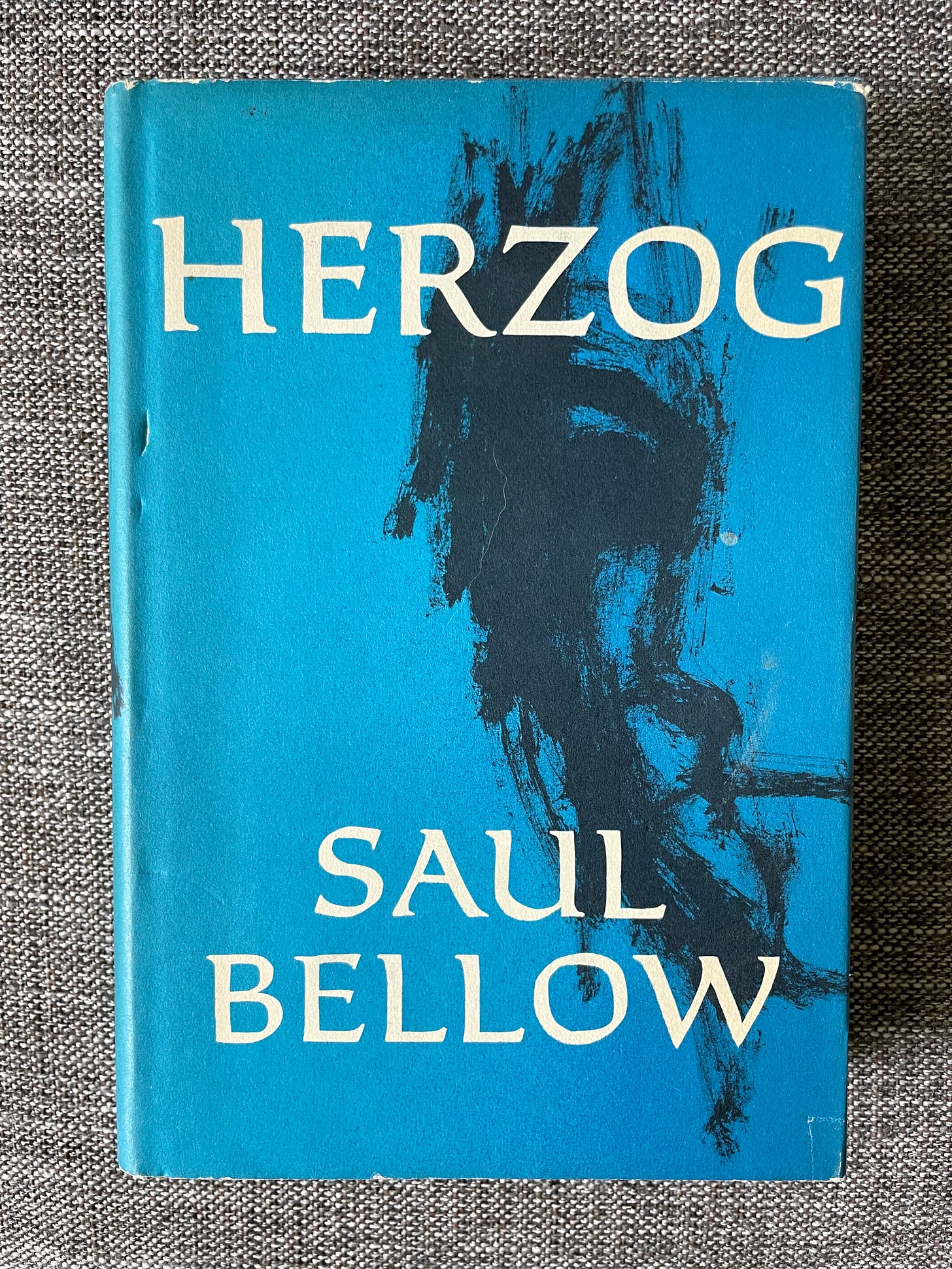

Chicago, June 2015

At the risk of becoming known on Lit Substack as The Saul Bellow Girl(TM), I have some more Bellow-posting for you today.

In the Spring quarter of my senior year at the University of Chicago, I was burnt out from a couple of years of grinding through challenging applied and pure math classes, plus working on my bachelor’s thesis for the Classics major I declared very late in my junior year. I decided I wanted to end my college career on a lighter note that catered to my natural strengths, so I took two fun literature classes, both taught by instructors from the Committee on Social Thought: Moby Dick; and Novels of Individualism: The Bildungsroman in English.

For the latter class, we read an eclectic mix of books. As far as I can recall, the syllabus included A Portrait of the Artist As A Young Man by James Joyce, Mao II by Don DeLillo, and Herzog by Saul Bellow. (I’m certain there were others, but these are the books I remember.) Herzog, in particular, was a revelation; it’s one of the books that changed me on some subtle, cellular level. Herzog cracked something open in me. I had a feverish/ecstatic experience while reading it, and it even compelled me to (briefly) exit my relationship with a much-older narcissistic abuser.

In honor of my tenth anniversary of reading Herzog, I unearthed my final paper for that course from an old hard drive, in which I perform a close reading of a nursery rhyme that is repeated throughout the novel. I thought it would be fun to share it with y’all. I audibly gasped when I saw the title I gave it, which I had erased from my memory. Truly unhinged of 21-year-old Lillian, but I guess it all worked out. (I received an A- in the course; most of the grade came from this final paper.)

Reading through it now, a decade later, I’m pleasantly surprised at its quality. I thought it would be much more embarrassing. It starts a little slow but by the end I’m cooking. But I’ll let you decide for yourselves.

Note that, insofar as a book like Herzog can be ‘spoiled,’ this essay contains spoilers.

Pussy: the Eroticization of Children in Saul Bellow’s Herzog

Lillian Selonick

ENGL 20699: Novels of Individualism: The Bildungsroman in English

June 5, 2015

Herzog the man and Herzog the novel are both preoccupied with women. Moses Herzog narrativizes his personal and professional failures as following from his intimate relationships. This preoccupation with sex is not limited to Herzog’s own individual life. Sexual problems—and solutions—are proposed as the source of the largest of modernity’s issues. What space can there be for the young daughter of a bachelor who constructs or perceives such a world? Consistently Herzog returns to the theme of innocence, declaring himself an Innocent Party, yet he repeatedly fails to find naïveté in girl-children. In the juxtapositions of a recurring nursery rhyme with memories or experiences with varying sexual valences, the tension between the innocence of youth and the specter of puberty and subsequent bitchhood is illustrated with striking precision.

Herzog, good academic that he is, finds the problems of contemporary life to be deeply intertwined with the invasion of private sexual life by the state. This position itself is arguably a projection of Herzog’s sexual assault as a boy—the Innocent Party, the innocent individual, is helpless as a faceless figure, a grown-up, an authority by default, violates him. In his letter to Eisenhower, Herzog laments that “Public life drives out private life…. The whole matter is of the highest importance since it has to do with invasion of the private sphere (including the sexual) by techniques of exploitation and domination” (178). In a letter to one of the most public men in America, Herzog finds it necessary to specify, parenthetically, that sex is a part of the private sphere.

These parentheses are telling. Bellow later draws attention to the importance of the aside by cheekily inserting an illustrative parenthetical as Herzog grapples with his emotional reunion with June. “One of his units of mental extension swelling and passing, a lengthy aside (Much heartbreak to relinquish this daughter. To become another lustful she-ass? Or a melancholy beauty […….]), departed with another of those twinges” (299). Bellow seems to suggest that the parenthesis is one of Herzog’s essential modes of thought. Larges pieces of the novel are parenthetical asides, nested narratives within letters or long moments of reflection during Herzog’s contemporary lived experiences.

In the midst of a memory of his early relationship with Madeleine, embedded in a letter to Monsignor Hilton, the Catholic priest who converted her, Herzog pauses to recall their daughter’s favorite nursery rhyme. The immediate context in which the rhyme is introduced is a reflection on the manliness of Herzog’s character:

“I thought it might interest you to learn the true history of one of your converts, Monsignor. Ecclesiastical dolls—gold-threaded petticoats, whining organ pipes. The actual world, to say nothing of the infinite universe, demanded a sterner, a real masculine character.

Like whose? thought Herzog. Mine, for instance? And, instead of concluding this letter to Monsignor, he wrote out, for his own use, one of June’s favorite nursery rhymes.

I love little pussy, her coat is so warm

And if I don’t hurt her, she’ll do me no harm.

I’ll sit by the fire and give her some food,

And pussy will love me because I am good.

That’s more like it, he thought. Yes. You must aim the imagination also at yourself, point-blank” (129-130).

The rhyme recurs, in various levels of completion, twice more, on pages 239 and 317.

The nursery rhyme operates on a few different levels. Herzog writes this letter out of malice for Madeleine, displaced onto the Monsignor. The priest is a sexual rival in the sense that his conversion of Madeleine compels her to dampen her nubility and turns her affair with Herzog into a shameful practice. The nursery rhyme abruptly truncates this letter, presenting a pure counterpoint to the erotic hostility of the letter. June here seems to act as a tonic for Herzog’s malice, but the fact that she occurs to him at all during this moment of hatred and meditation on masculinity demonstrates the inextricability of his daughter’s purity from the jealousy and sexual rivalry that characterized his relationship with Madeleine from the beginning.

The rhyme also serves as an answer to Herzog’s question: “Mine, for instance?” But the answer is ambiguous. Multiple meanings of the word ‘pussy’ complicate the matter. First, in the context of the nursery rhyme, it means ‘cat.’ But this, its innocent definition, cannot be divorced by a 20th or 21st Century reader from its euphemistic reference to female genitalia. Its appearance in the book is all the more jarring for its being embedded in what ought to be the most innocent of contexts. Outside of the rhyme, and a sobriquet granted to June, Herzog does not use ‘pussy’ in any of its other senses. The word’s exoteric role in this complex text is conspicuously, intentionally nonsexual—and it is the very careful asexuality of Herzog’s use of the word that attaches the more vulgar meaning to it so strongly.

Pussy also seems to metonymically refer to Madeleine. And if I don’t hurt her, she’ll do me no harm. There is a hidden darkness to the rhyme. The conditions for not being harmed by little pussy are specified, implying that action must be taken to avoid harm, that violence is pussy’s nature. Herzog did hurt Madeleine, and she retaliated fiercely.

The variants present in later moments illustrate the different aspects of Herzog’s focus as the novel progresses. In its second iteration, as Herzog meditates on justice for the adulterers, the second line is excluded: “I love little pussy her coat is so warm, and I’ll sit by the fire and give her some food, and pussy will love me because I am good” (239). This recitation occurs after Moses remembers repeatedly forcing Madeleine to have sex on the bathroom floor in Ludeyville, knowing that this enraged her. This is the ‘hurt’ he inflicts, and excising it from the rhyme is a reflection of his reenactment, in memory, of this hurt. It is an omission that is conspicuous because it distorts the rhyme by mutilating the first couplet. The collapse of structure from the initial presentation on page 130, in which the rhyme is typographically offset from the rest of the text, into a single run-on sentence, is at once a way of integrating the verse more fluidly into Herzog’s stream of consciousness and of disguising the missing line.

To what end is the second line excluded from page 239? It comes at a turning point in Herzog’s running monologue, in which he recognizes the absurdity of considering himself an innocent deserving of justice.

“Why, let them alone. But what about justice?—Justice! Look who wants justice! Most of mankind has lived and died without—totally without it. People by the billions and for ages sweated, gypped, enslaved, suffocated, bled to death, buried with no more justice than cattle. But Moses E. Herzog, at the top of his lungs, bellowing with pain and anger, has to have justice. It’s his quid pro quo, in return for all he has suppressed, his right as an Innocent Party. I love little pussy her coat is so warm, and I’ll sit by the fire and give her some food, and pussy will love me because I am good. So now his rage is so great and deep, so murderous, bloody, positively rapturous, that his arms and fingers ache to strangle them. So much for his boyish purity of heart” (239).

The conditional of the second line, if I don’t hurt her, has not been met, and becomes irrelevant in Herzog’s mind. He has hurt little pussy and been harmed in return, as promised. His focus instead shifts to that of his role as provider. While not a wealthy man, he does support Madeleine, and resents her for failing to reciprocate what he perceives as her role in the relationship.

Even more than “giving her some food,” Herzog expects Madeleine to love him because he is Herzog, “because I am good.” The converse seems to be true, he decides in the next few sentences. Because little pussy does not love me, I am not good. This gendered innocence is key; a “boyish purity” is, to Bellow, distinct from girlish purity. Herzog, after imagining murdering Madeleine and Gersbach, cannot continue to conceive of himself as pure.

The innocence of children appears in a number of forms throughout Herzog. Notable is the abuse suffered by the boy who was murdered by his parents—he was beaten about the genitals. After witnessing an earlier case in the same courthouse, Herzog comes to this conclusion: “Sexual practices of any sort, provided they didn’t disturb the peace, provided they didn’t injure minor children, were a private matter. Except for the children. Never children. There one must be strict” (247). It is a sensible line to draw, certainly, but the syntactical emphasis betrays a deeper emotional investment. And yet, the denial of the innocence of female children is seen through Moses’ examination of photographs of his lovers.

As a reader, at this point in the novel, one might suppose that this reaffirmation of the criminality of pedophilia was in response to knowledge of Madeleine’s assault. Indeed, it is just before the initial nursery rhyme where Herzog discusses the mystery of Madeleine’s sexual trauma at age fourteen. Yet it is just a few pages after this that Herzog denies Madeleine the innocence of youth: “Moses, a collector of pictures, had kept a photograph of Madeleine, aged twelve, in riding habit…. In jodhpurs, boots, and bowler she had the hauteur of the female child who knows it won’t be long before she is nubile and has the power to hurt. This is mental politics. The strength to do evil is sovereignty. She knew more at twelve than I did at forty” (138). Herzog attributes Madeleine’s cruelty to an essential femininity, rather than abuse—her ‘mental politics’ predate her assault.

Even sweet Ramona is not immune to these judgments. Herzog looks at a picture of Ramona at age seven: “Pierced ears, a locket, a kiss-me curl, and the kind of early sensuality in tiny girls which he recalled very well” (201). This recollection of ‘early sensuality’ does not appear in the novel. The only tiny girl with whom Herzog experiences this sensuality is his own daughter June: “And she with all her innocence and childishness and with the pure, or amorous, instinct of tiny girls, kissed him on the lips, her careworn, busted, germ-carrying father” (298). June is younger than Ramona in the picture, but her gender already haunts Herzog. The “pure, or amorous, instinct” is apparently none other than the infamous Oedipal attachment. Bellow’s confused attribution of adjectives to June’s kiss implies that Herzog harbors a desire to see his own erotic relationship to June as reciprocal in some rudimentary sense.

The language surrounding the father and daughter reunion is highly erotic. “One of his units of mental extension swelling and passing, a lengthy aside (Much heartbreak to relinquish this daughter. To become another lustful she-ass?... ), departed with another of those twinges” (299). This swollen extension recalls the eternal erection of Man Herzog believes demands to be satisfied as he awaits Ramona’s embrace. On the conscious level, he has already begun to see the enemy emerge to transform his pure child into a vicious sexual animal.

Later, in the police station, Herzog unconsciously closes the circle, defining a relationship between June and Madeleine. He surveys the latter’s apparently enlarged rear with some satisfaction: “He observed that she was definitely broader behind. He imagined what clutching and rubbing was the cause of that. Uxorious business—but that was not the right word… Amorous” (324). Here Herzog again fumbles with the correct words, landing again on ‘amorous’ as he did with June.

The nursery rhyme emerges once more as Herzog’s interaction with June and the police unfolds. First, he calls June “Pussy-cat” just once as a term of affection (303). This is in general an unsurprising nickname; especially considering that I love little pussy is June’s favorite nursery rhyme. However, it is a highly marked word—used a single time, its first letter capitalized. Several pages later, he recites the rhyme for the last time, reflecting on Sandor Himmelstein’s vulgarity—this is the man who charmingly produces the phrase “the bitches come and the bitches go” (88) (to which one might feel compelled to add: talking of Michelangelo).

“I shouldn’t look down on old Sandor for being so tough. This is his personal, brutal version of the popular outlook the American way of life. And what has my way been? I love little pussy, her coat is so warm, and if I don’t hurt her she’ll do me no harm, which represents the childish side of the same creed, from which men are wickedly awakened, and then become snarling realists” (317).

Unlike the “Pussy-cat,” the rhyme becomes progressively less marked with each iteration. It is increasingly incorporated into Herzog’s thought processes. Here it is unitalicized, shown to be an explicit answer to the question posed earlier, concerning the masculinity of Herzog’s character. What is Herzog’s way in the world? Naïveté, a precarious relationship to women, victimhood. This version of the rhyme excludes the second couplet about food and love; at this point, Herzog is not immediately concerned with his role as provider or any of his responsibilities as a husband. Instead, the more passive first couplet, the one that indicts women as possessing inherently violent natures, is the only one that comes to his mind.

Sandor, it must be remembered, is the father of daughters whom he terrorizes, at one point hoping to marry his eldest—of an unspecified, but much too young, age—to Herzog. He also pleads with Herzog to educate her, a collapse of pedagogy and eros that recalls the institution of Greek pederasty. This institution, in a perverse form, is evoked again as Herzog rides in the back of the squad car with June on his lap. He remembers the stranger who assaults him as a boy—again, at an unspecified age. It is the non-penetrative nature of this intercural intercourse that resonates as a vulgar, exploitative performance of an erastes-eromenos relationship.

This language casts in an uncomfortable light the paternal tenderness the reader experiences with relief after hundreds of pages of Herzog’s internal vitriol. But Herzog is clearly not a predator. He has no overtly prurient intentions towards his daughter. Instead, Bellow seems to be pointing at a more universal experience, the tension between fatherly and romantic affection within a still-virile man. This tension is particularly present in Herzog’s life because of the generational difference between Moses and Madeleine. The eternal refrain of reproach fits here: Herzog is at least physiologically capable of being Madeleine’s father. As the novel unfolds, this tension becomes more pressing. Herzog’s specific erotic relationship to June is simply the most extreme enactment of the hostile world philosophy he has developed through the traumas and the pleasures of his sexual life. This philosophy is ultimately expressed through the nursery rhyme: Herzog is bitter and mournful, enraged and puzzled, unable to resolve the problem of childish innocence and the mysterious mechanism by which a child becomes the enemy, by which tiny girls become bitches.

For more of my (recent) writing on Saul Bellow, check out the posts below:

On Dangling Man:

On Bellow’s 5 marriages and terrible love of women:

On Humboldt’s Gift:

On Seize the Day:

If you enjoyed this post, please consider hitting the like button, subscribing if you haven’t already, and leaving a tip via Buy Me A Coffee if you’d like to show your support but don’t want to commit to a paid subscription. Thank you for reading!

Lillian you are not helping my effort to look like a normal man™ when this email popped onto my work screen

(fantastic as always tho)

You've reminded me how many levels this book has (and I re-read it about a year and a half ago, so it's still somewhat fresh in my mind).

An overall impression is that Bellow is playing throughout the book with the tension between Herzog's high-minded image of himself as a Romantic intellectual and the muck and pettiness of real life that he constantly gets dragged into. At any rate that's one of the things that appeals to me about it.

BTW not sure about this but I think he got the name Moses Herzog from Chapter 12 of "Ulysses," the pub chapter, sometimes known as "Cyclops."