The Revolution took on largely the character of religion. We worshipped at the shrine of the Revolution, which was the shrine of liberty. It was the divine flashing through us. Men and women devoted their lives to the Cause, and new-born babes were sealed to it as of old they had been sealed to the service of God. We were lovers of Humanity. (167)

For some unknown reason, I’ve been thinking about fascism a lot lately. With strongmen rulers popping up like a depressing, gold-plated game of whack-a-mole, an attempted self-coup in South Korea last week, and Trump’s clown car of political appointees dominating the news cycle, I hoped that turning to the past might be instructive. As such, I read Jack London’s 117 year old novel The Iron Heel, which envisions a future both darker and in some ways more hopeful than our current boring dystopia.

This is not your grandmother’s Jack London. I had never heard of The Iron Heel until earlier this year, when my husband was researching the history of dystopian fiction. When I was very young, I read White Fang and The Call of the Wild. As a suburban kid who never went camping, these books of the Western frontier spoke powerfully to my imagination. I spent more time trying to speak to animals than to other humans as a kid, and some small part of me still believes that one day, the animals will start talking back.

I didn’t return to Jack London for over twenty years. I thought I knew about he was all about: nature, adventure, and rugged individualism on the West Coast at the turn of the 20th Century. What I didn’t know is that a) he was a massive socialist and b) he wrote a speculative fiction novel in 1907 that is essentially a future history of 700 years of capitalist oppression and socialist resistance.

The most remarkable thing about The Iron Heel is its structure. It takes the format of a memoir written by Avis Everhard, wife of an American leader of the socialist revolution and herself a leader in the socialist organization. Her husband, Ernest Everhard (god-tier name for a baby boy and/or dog, fyi), led the failed First Revolt in the 1920s against the oppressive plutocratic regime known as the Iron Heel. This regime executed Ernest in 1932. Avis, writing not long after his death, is anticipating the success of an international Second Revolt in the near future.

However, the Second Revolt also fails and the brutal repression under the Iron Heel lasts for another 300 years. We know this because Avis’s memoir is presented as an historical document, complete with explanatory footnotes throughout, for students and scholars of the 20th century in a socialist utopia about 700 years in the future. All of this background is revealed within the first few pages, so I promise you these are not spoilers. It’s all just the mind-blowing framing for this remarkable book that feels fresh and innovative despite its age.

I’m a total slut for fiction with footnotes and endnotes. I read Pale Fire by Nabokov (endnotes) and The Third Policeman by Flann O’Brien (footnotes) when I was 15 and they blew my little mind. In the former, the story unfolds primarily through the endnotes to a long poem, at turns poignant and darkly hilarious. In the latter book, the footnotes digress from the already outrageous plot to expound on the narrator’s scholarship on a very wrong natural philosopher’s theories as an additional layer of comedy. When a silly footnote about de Selby’s stupid theory about atoms takes up most of the page? Love it. So I was primed to be charmed by Jack London’s footnotes, some of which relay real historical information about the rise of an oppressive capitalist class while others describe the conditions of a fictional future. I am utterly delighted that this book exists.

(Just to put all my cards on the table— yes, I love Infinite Jest, I’m sorry if that makes me an obnoxious lit bro. No, I’ve never read House of Leaves, but I’ll get around to it some day. No, I didn’t know until I asked ChatGPT today that Tristram Shandy by Laurence Sterne was the first novel to incorporate footnotes, and no, I haven’t read it (yet). Tristram Shandy was just name-dropped in my current read, Good As Gold by Joseph Heller, so I’m thinking it’s a sign.)

The first half of The Iron Heel is a conversion story, the tale of young, upper-crust Avis’s introduction to working class iconoclast Ernest—and his politics— in her physics professor father’s home in Berkeley in 1912. As Avis falls in love with Ernest, she embarks on a journey of discovery of class consciousness. When she comes to understand how her high society lifestyle is made possible only through the violent exploitation of workers, Avis becomes an ardent socialist. At this point, the plutocratic takeover of the United States that began in the 19th century is closing in and there is increasing consolidation of wealth in all industries, but the Socialist Party is making significant electoral gains. It seems like there’s a real chance to improve life for the great proletarian masses.

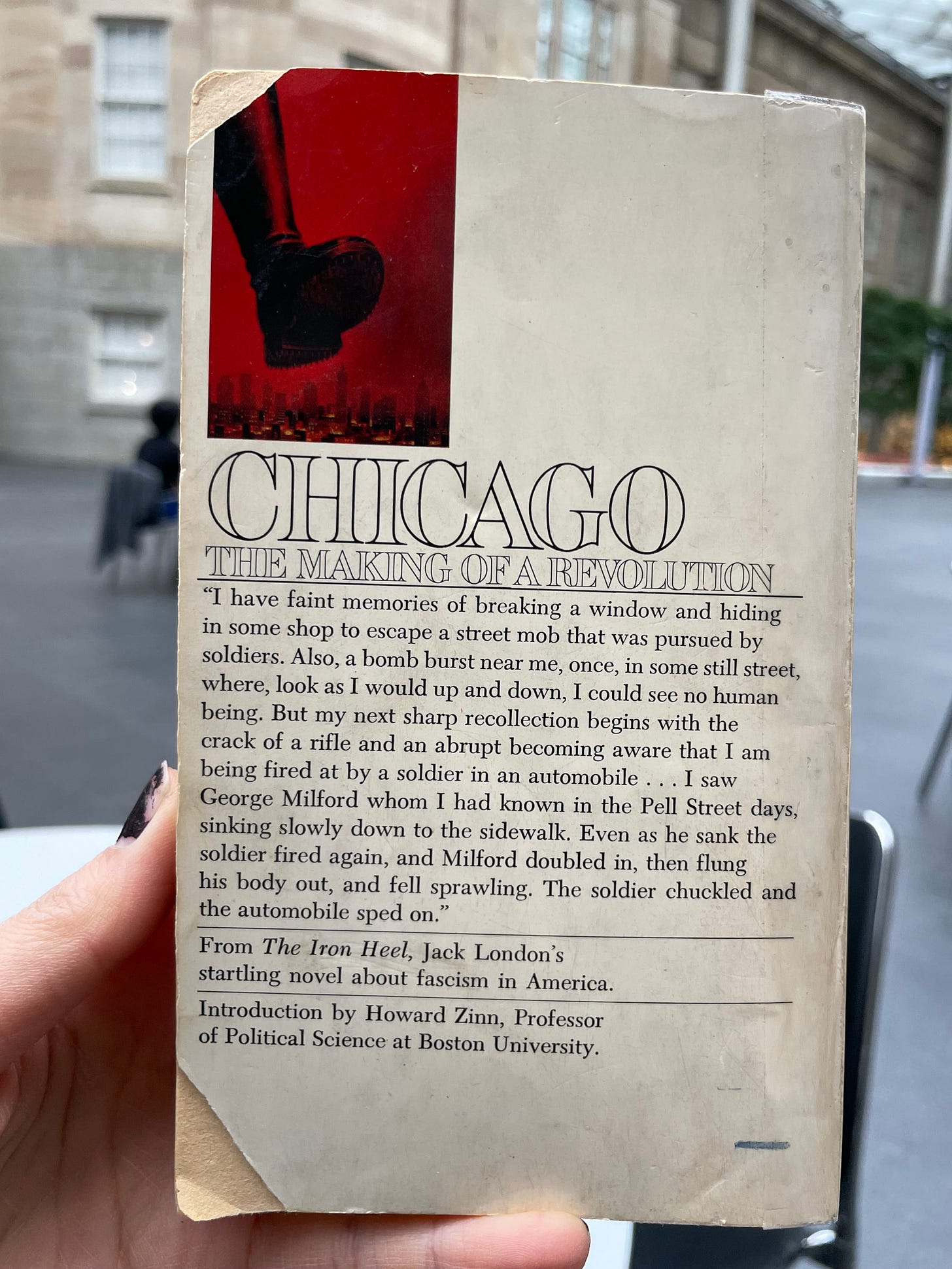

In the second half, those gains evaporate as the Iron Heel declares open war on the Socialists. The book traces the Everhards’ arc from civil agitators to armed revolutionaries as the oligarchic noose tightens around America’s neck. The story culminates in the violence of the Chicago Commune, a nightmarish clash between the regime, the revolutionists, and the great teeming masses of the illiterate, unwashed underclass that are caught in between. It’s a clear reference to both the Paris Commune of 1871 and the Haymarket massacre (in Chicago) of 1886, events that would have been recent history to London writing in 1906. The Chicago Commune is teased throughout the book (and prominently on the front and back covers of my edition!), and the thrilling account we get in the final chapters is a worthy payoff.

The book is completely unsubtle and reads like a propaganda pamphlet at times. Ernest Everhard is smug and pedantic when he lectures to rooms full of flustered Berkeley elites, and Avis, as the narrator, can be irritatingly naive. The footnotes can get a little cutesy as they explain basic concepts about this barbaric capitalist society to the utopia-dwelling reader, like the concept of debt or trusts.

But, if I’m being honest, I found these weaknesses to be more endearing than annoying. I loved the vigor and clarity that London brings to his beliefs. I felt this way about The Jungle when I read it in high school— it’s a gripping, overwrought story of the horrors of life in the Chicago stockyards that transforms into a naked socialist screed for the last portion of the book, and I was utterly swept up by it.

Like most millennials, I’m a little bit of a socialist, having come of age in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis and borne witness to *gestures vaguely* all of this. I’m also a folk music nerd who interned at Smithsonian Folkways Recordings and has a soft spot for the drama of early 20th century labor struggles as interpreted by Woody Guthrie, Paul Robeson, et al. But 21st century socialism comes with a lot of baggage, and about 20 million caveats that must be made. London, in 1907, was completely unburdened by all that was to come in the 20th century. It’s pleasant to be immersed in that moment of hope and moral clarity, before left and right wing totalitarianism. Even though his vision of the mid-future was bleak, the Iron Heel contained the seeds of its own destruction and the far-future was an inevitable paradise.

It’s disappointing (to the part of my spirit that is still stirred by such ideas) to consider that the kind of armed insurgency the Everhards organize is not viable in our modern information environment. It’s too hard to sustain a conspiracy and anonymity, and the number of people who are truly willing to put their freedom and lives on the line for an idea is too small. Howard Zinn, writing in his introduction to the book in 1970, laments the uselessness of electoral politics and armed resistance:

In the modern, powerful, industrial state both these tactics—voting and armed insurrection—are decoys. The ballot box, a tawdry token of democracy, enables shrewd, effective control in the mass society, by those on top. And armed revolution is so clearly suicidal against the power of the great national state, that we must suspect its advocates of being police agents… (xii-xiii)

As I write this, Luigi Mangione, who allegedly assassinated the CEO of UnitedHealthcare, has just been arrested. He was identified by a McDonald’s employee in Altoona, PA. A McDonald’s employee. A prole making $13.40 an hour sided with the oligarchs and turned him in. Our Iron Heel doesn’t need to mow down striking workers in the streets. They’ve perfected a more effective means of control. They’ve convinced us all that, some day, we might be rich, too, if we work hard and keep our heads down.

The Revolution is dead. Long live the Revolution.

8.1/10

Yours is the first review I've seen of this book. I bought it back in 2013, but never got around to reading it. But I was working back then. Now might be a good time. And I totally agree that footnotes in an untranslated novel are a turn-on.

First, thanks for bring this element of London’s work to my attention. What a mind blowing structure for an early 20th Century work.

My take on Luigi is that he is a murderer. He will be punished for an inexcusable act which has brought agony to his family …and to the family and friends of his victim. That said, given the explosion of social media surrounding his likely motivation, his act may just have had its intended effect: to spark appropriate outrage at our insane medical insurance system. May he be viewed as a saint 100 years from now…